WALLA WALLA, Wash. — Celebrate Walla Walla Valley Wine organizers didn’t need to go far to find perhaps the best person in the world to compare Walla Walla Valley terroir to that of Napa Valley.

Kevin Pogue, professor of geology at nearby Whitman College, served as the opening presenter as the Walla Walla, Wash., event. In the past decade, he’s also developed into a consultant sought after by grape growers and winemakers throughout the region, so it made sense to have him speak at the Powerhouse Theatre regarding how geology, climate and soils influence grape growing and winemaking two of North America’s most wine regions.

Kevin Pogue, professor of geology at nearby Whitman College, served as the opening presenter as the Walla Walla, Wash., event. In the past decade, he’s also developed into a consultant sought after by grape growers and winemakers throughout the region, so it made sense to have him speak at the Powerhouse Theatre regarding how geology, climate and soils influence grape growing and winemaking two of North America’s most wine regions.

“I was run out of northwestern Pakistan by terrorists and now I am a terroirist,” Pogue told the audience. “There’s irony there.”

His 21-minute presentation helped define “terroir” for those in the theater, and the Kentucky native said he appreciated the opportunity to drill down on the topic that includes geography, soil and climate.

“Terroir, it’s a very misunderstood concept and utilized by the press a lot of the times in ways maybe it shouldn’t be,” Pogue said.

While many of his peers have no problem defining terroir, describing the Walla Walla Valley is different, he said.

“For the last eight years, I’ve been going to Europe for the International Congress in Terroir, where about 300-400 terroirists meet and discuss the signs of terroir. Generally, I’m one of two or three Americans there.

“The question I always get is, ‘Where is Walla Walla? And what kind of grapes do you grow there. Most Europeans know wines from the United States, but they only know Napa Valley. And they always want to know, ‘Well, how do you compare to Napa Valley?”

Pogue, who speaks at Northwest wine industry events such as the Washington Association of Wine Grape Growers and Taste Washington, titled his Celebrate Walla Walla program ‘The Tale of Two Terroirs.’

“There are many terroirs in each place, and it’s not a simple thing of saying, ‘This is Napa and this is Walla Walla, and this is how they are different,” he said. “It’s like trying to describe the differences between San Francisco and Seattle. They are big and complex places. There are neighborhoods. If I’m comparing Seattle to San Francisco, do I compare Capitol Hill to the Castro or Ballard to the Mission District?”

Those neighborhoods could be akin to the establishment of American Viticultural Areas by the federal government, a declaration similar to appellations in France.

“Those are based on terroir hopefully, although marketing plays a huge influence,” said Pogue, who has written the application for the Walla Walla Valley’s first sub-appelation, The Rocks of Milton-Freewater.

“I designed it to be what I think is the most single-most terroir-driven AVA in the United States,” Pogue said.

And there are many layers of complexity to the AVAs of Napa and Walla Walla.

“Anyone who knows Napa Valley knows that Carneros is a much more different places to grow grapes than, say, Mount Veeder and have different characteristics,” Pogue said.

The same can be said for more than just the proposed “Rocks” of the Walla Walla Valley.

“We have a lot of potential to break ourselves out into regions over time,” Pogue said. “Looking east toward the Blue Mountains of Walla Walla Valley, we have very different terroirs. We have the valley floor, we have alluvial fans. We have steep canyon walls, and we have the foothills of the Blue Mountains.”

That “physical terroir,” Pogue called it, plays a major role in determining what type of grapes should be planted where. Elevation and latitude are among those factors. The Walla Walla Valley AVA ranges from 400 to 2,000 feet of elevation. In Napa, it ranges from sea level to 3,000 feet.

At that pont, he showed a slide about latitude, which explains why the summer solstice effect on the Walla Walla Valley traditionally means 56 more minutes of sunlight.

“I always have to get in a little dig at my friends in Napa,” Pogue said. “In Walla Walla, our nearest neighbors are Bordeaux and Burgundy, and their neighbors are in Etna (on Sicily) latitudinally,” which created laughter. “So they are pretty far south for a wine growing region in Europe.

He closed that topic by adding, “It’s not a good comparison.”

There’s definitely room to grow in the Walla Walla Valley, and Pogue seems positioned to help.

“Napa Valley has 45,000 acres planted or 11 percent of the AVA, and we have 1,700 acres, which is 0.5 percent,” Pogue said. “We have a lot more room to plant — if I can help you find all those good places to plant.”

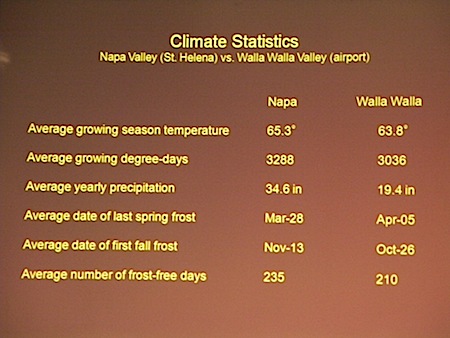

When it comes to climate, each region excels for different reasons.

“We have a more continental climate,” Pogue said. “We have a lot less precipitation, and we’re a little bit cooler.

At that point, he described the continentality.

At that point, he described the continentality.

“It’s a way to measure our biggest difference,” Pogue said. “We have a stronger contrast between the seasons. It gets colder here and warmer in the summer. The change of seasons is a lot faster, and causes us to have these scary frost events — like we had a few in April.

“It’s not as big of deal in Napa because their climate is moderated by the proximity of the Pacific. San Diego is probably the place in the United States that has the lowest continentality – the lowest variation between seasons.

In July and August, Walla Walla surpasses Napa Valley in terms of average temperature. However, Walla Walla is considerably colder in the winter.

And in terms of precipitation, the Napa Valley gets 26-30 inches per year.

“Every place in Walla Walla gets much less than the driest place in Napa Valley,” Pogue said. “We are farther from the ocean, we’re not as close to the moisture supply.

“What we don’t have here and Napa does have that’s a big influence on their climate is coastal fog,” he added. “It does a lot to cool Napa Valley in the mornings and keep it from getting as hot as it might.”

All in all, the Napa Valley enjoys a three-week growing advantage, “but it’s still long enough to ripen the grapes,” he said.

Perhaps the most important difference between the two regions comes down to soil types. Those soils, combined with the cold winter, keep the wine industry’s most heinous pests out of the Columbia Valley.

“We don’t have phylloxera here, which is a very nasty little bug that kills grapevines,” Pogue said. “North American grape varieties are resistant to it, and most grape vines all around the world are grafted on to North American roots. We are one of the largest areas in the world where grapevines are growing on their own roots.”

And there’s the fascinating story of how the Walla Walla Valley got its soil.

“In the Walla Walla Valley, we have basalt, Ice Age floods sediment and wind-deposited silt and Napa Valley has very complex geology associated with movements of the San Andreas Fault,” he said. “Being a very active geologic area, they have several fundamentally different kinds of bedrock.

“The soils of the Napa Valley are the result of millions of years of breakdown of the bedrock, a traditional soil forming process where the rock slowly decayed by weather — and soil is produced.”

It’s the search of terroir that continues to help shape and define the Northwest wine industry.

“Vineyards have been put in to take advantage of all these different terroirs,” Pogue said.

“I designed it to be what I think is the most single-most terroir-driven AVA in the United States,” Pogue said.

With all due respect, as I think Dr. Pogue is doing great things by getting more people to consider soil and how very important it is for quality grape growing. Though I think when we talk about terroir, including the influences of weather, we must not overlook the water source. I would have to ask, without irrigation, how well do the vineyards in Walla Walla perform?

I don’t know where the greatest terroir in the U.S. lies, or if we have found it yet, and with climate change I think that will be an evolving answer. I do think however, if we are to judge terroir, a naturally applied water source is right up there in terms of importance with soil, sun, and other weather factors. I don’t think you can separate the elements of terroir and still have perfect terroir. I don’t know if a grand terroir exists, but if it does, I think it will have great soil, exposure, and weather, including a naturally occurring water source.

Sincerely,

Chris Dickson

ITB

Willamette Valley, OR

Hi Chris-

I completely agree that the best expression of terroir would come from non-irrigated vineyards, and we actually do have non-irrigated vineyards in the Walla Walla Valley – but not in the rocks region, which hosts the proposed AVA. However, I stand by the comment I made in my presentation. The boundaries of our proposed AVA enclose a relatively small area with exceptionally uniform soils, topography, and climate. Even though the vines are irrigated, I believe that all of the grapes coming from this AVA will share a uniformity of source that is unique among US wine growing regions. In a perfect natural-wine terroir world, we’d all make wine from wild non-irrigated grapes growing in the branches of trees (their natural habitat). The grapes would spontaneously ferment in earthen jugs, and we’d drink the wines fresh without sulfur additions or oak-barrel aging. Only then would would we taste “real” wine – as free from human intervention as possible. Once we plant vines, trellis them, prune them, leaf strip, hedge, cluster thin, apply sprays, we’re altering nature’s course and are on the road manipulating the final product – and moving away from an expression of terroir. Of course, the manipulation really accelerates in the winery with cold soaks, yeast additions, oak, mega-purple, etc., etc. My point is, with terroir expression, it’s a sliding scale. Most vineyards in the main grape-growing regions of the western US are irrigated, but most of the AVAs encompass a host of physical terroirs. The boundaries of our proposed AVA were constructed with the intent of creating a more uniform expression of terroir from the wines made from grapes grown within. Perhaps irrigation dilutes (sorry) this effort a bit but it doesn’t negate it.

Thanks for the response Dr. Pogue, I really appreciate it. I see your point regarding ‘physical terroir’ and how you have found a unique pattern of soil in the rocks worthy of distinction.

First, I think we need more folks out there like yourself scavenging for special soils. Important and fascinating finds await. I also agree about the many manipulations we have at hand to ‘make’ wine and how it can all really amount to crafting a product.

I do however find trellising, thinning, sulfur sprays, tilling, pruning and other similar measures to be ways of adapting to a particular vintage, including the vine’s relationship with the soil and the particular weather imprint of a specific vintage.

Though I have little doubt that farming can be difficult in Eastern WA (frosts, etc.) and steps must be taken for quality fruit to grow, I wonder if growing grapes in the desert with irrigation as an absolute necessity doesn’t somehow begin in error or in a forced manner?

I won’t challenge the absolute uniqueness of soils you have under the vines, but I find this environment to provide the vines little room to be adaptable in searching for life amongst the soil , a crucial aspect of what I consider expression of terroir.

There are a host of ways for us to stress or protect the raw material before it reaches the cellar, where of course it can be further shaped or lost. I feel these are all secondary manipulations, whereas the necessity for irrigation in an unsuitable climate for grapes I believe is an artificial intervention that changes the nature of terroir and subsequently the fruit that grows. I can’t help but think of a lawn grown in Tucson, or a wave pool in Kansas.

I work with vineyards that are both irrigated (limited) and dry-farmed, and with regard to the sliding scale of terroir that you mention, I do see the powerful combination of soil, topography, sun and climate. Certain vineyards do better than others in a given vintage because of any combination of these factors, though the vineyards that really wear their stripes are of the non-irrigated type. The stress they show is a reflection more of vintage, one which involves lots of adaptation through time. The quality raw material simply can’t be replicated by timely water intervention in my opinion.

Though maybe it’s just me, but I put a lot of value on Vintage, where inconsistency is a goal and not something to avoid. Single-most terroir driven AVA, in a Desert? Quite possibly. In the U.S.? Not the way I see it.

– Chris Dickson