ASHLAND, Ore. — World-renowned climatologist Greg Jones of Southern Oregon University issued his season-ending report Wednesday, which compared the 2013 grape growing season for Oregon vineyards to that of the 2003 warm vintage.

The Ashland professor in environmental science used data from four weather stations throughout Oregon to support his findings.

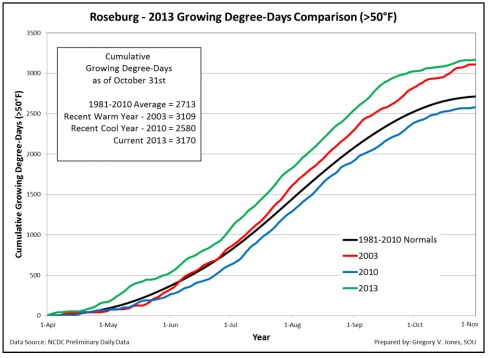

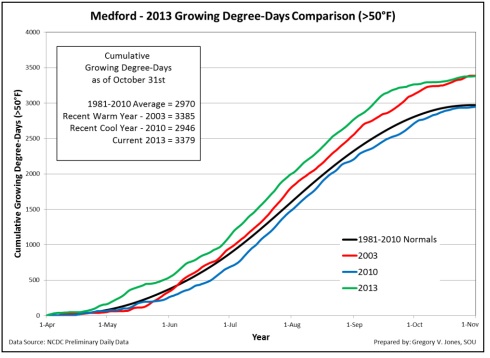

“Medford, Roseburg and Milton-Freewater ended up right at or above the warm 2003 vintage, with McMinnville ending the month slightly below that experienced in 2003,” Jones wrote. “For those in Oregon, the final month in the season brought our growing degree-day accumulation to a close, with values 3-13% above 2012 and the average of the last 10 years.”

The Willamette Valley weather station in McMinnville — Jones’ benchmark for Pinot Noir country — finished the reporting year Oct. 31 with a recording of 2,428 cumulative GDD, a frame of reference for growing when the temperature surpasses 50 degrees Fahrenheit.

In 2003, the total came in at 2,602. That compares to the cool vintage of 2010, which finished with 1,853 GDD. Last year, the season-ending figure was 2,239.

In 2003, the total came in at 2,602. That compares to the cool vintage of 2010, which finished with 1,853 GDD. Last year, the season-ending figure was 2,239.

Milton-Freewater in the Walla Walla Valley ended at 3,466 GDD. A decade ago, that total was 3,484, while the average from 1981-2010 was 3,020. Last year, the total was 3,127.

This year, Roseburg’s growing degree days surpassed those of 2003 by a 3,170 to 3,109 margin. Last year, the figure was 2,805.

In Medford, the 2013 total of 3,379 nearly matched that of 10 years ago (3,385) and last year (3,383).

“The difference between the 2003 and 2013 vintages was the last two weeks of September and the first week of October, which in 2003 were much warmer,” Jones wrote.

“The difference between the 2003 and 2013 vintages was the last two weeks of September and the first week of October, which in 2003 were much warmer,” Jones wrote.

Jones pointed out the final three weeks of October proved to be a salvation for many of Oregon’s Pinot Noir producers.

“While October 2013 started off with the lingering conditions from the last two weeks in September, it eventually gave us a glorious stretch of clear dry days,” he wrote. “The conditions allowed growers to finish out harvest of any remaining fruit in relatively good conditions.”

By Halloween, the month finished up as being cooler than average throughout the West Coast. However, Jones’ four Oregon stations were 1.1 to 2.2 degrees warmer than normal through April to October. January through August was drier than normal across the Beaver State, with September being the only above-average month in 2013 — and all precipitation came in the second half of the month.

By Halloween, the month finished up as being cooler than average throughout the West Coast. However, Jones’ four Oregon stations were 1.1 to 2.2 degrees warmer than normal through April to October. January through August was drier than normal across the Beaver State, with September being the only above-average month in 2013 — and all precipitation came in the second half of the month.

“The shift from late September’s cool and wet to October’s clear and dry conditions came about from a blocking ridge of high pressure (called an omega block by climate scientists) where all storms coming  across the Pacific were pushed north into Alaska and Canada and then down into the Rockies and Midwest,” Jones explained. “These blocking ridges are common in the fall, a little more so in September than October, but this one was unusual in that it lasted for over two weeks. The result was generally cool nights, valley fogs in the morning, but clear cloudless days.”

across the Pacific were pushed north into Alaska and Canada and then down into the Rockies and Midwest,” Jones explained. “These blocking ridges are common in the fall, a little more so in September than October, but this one was unusual in that it lasted for over two weeks. The result was generally cool nights, valley fogs in the morning, but clear cloudless days.”

According to Jones, the models through the National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center indicate this winter will at least begin with a combination that’s cold and wet.

“The current CPC short term forecasts (6-10 and 8-14 days) through the end of the third week in November are pointing to a greater chance for cold and wet conditions due to a strengthening and southern path of the jet stream,” Jones wrote. “Extended out to 90 days, the CPC forecast does not have much guidance showing an equal chance for slightly above to slightly below temperature and rainfall conditions throughout the west.”

Conditions in the North Pacific make it difficult to ascertain any trends, which explain the fluctuations of September’s record-setting moisture and the extended dry spell in October, Jones said.

“Large variability in month-to-month weather is common in years where there is no clear signal in the tropical Pacific,” Jones wrote. “As I have mentioned before, La Nada years (when neither El Niño nor La Niña are present), can be the most volatile with wide swings in fall, winter and spring conditions.”

Leave a Reply