FRIDAY HARBOR, Wash. — It makes no sense for Chris Primus to be growing grapes and making wine on an island for San Juan Vineyards.

But the formula works, especially considering his lifestyle, a résumé that includes the late David Lake and the Ponzi family, and a formal education as a chemical engineer.

“Wine is something that you would want to put inside your body vs. distilling petroleum or making plastics,” Primus said wryly.

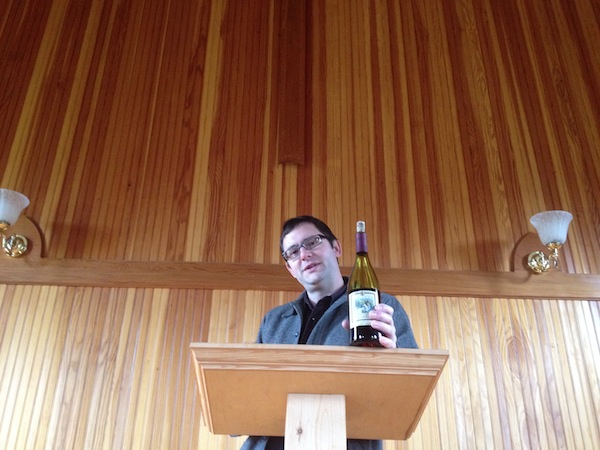

The San Juan Vineyards wines are poured inside a 1896 schoolhouse, and Primus’ work is worthy of ingesting — particularly at the dining table. There are gold medals with low-oak versions of Cabernet Franc and Merlot, grown in Washington’s Horse Heaven Hills. Primus’ signature wines, however, are Madeleine Angevine and Siegerrebe. They are aromatic and brilliant white wines that come off estate island vineyards he tends. Both also pair naturally with seafood.

“The Puget Sound does an amazing job with growing white wines,” Primus said. “With the cool climate, I think the volatile aromatics are held in the grapes. They are not burned off by temperatures, and the acids are maintained. They are beautifully expressive wines and grapes to taste on their own.”

Purdue chemical engineering student meets Dr. Vine

His unconventional path to the outer rim of winemaking in the Pacific Northwest began in the Midwest. Primus graduated with a chemical engineering degree from Purdue University in West Lafayette, Ind., but an elective requirement along the way landed him in a wine appreciation class led by internationally renowned Dr. Richard Vine.

A year later, Primus was at the University of Washington’s graduate school for chemical engineering when he was befriended by chemical engineering professor Charles Sleicher — among the cadre of 10 professors who founded Associated Vintners. Today, it is known as Columbia Winery.

“He was adjunct faculty at that time, and I talked to him about getting into the wine industry,” Primus said. “I always kind of thought about it. When we were in graduate school, we’d go to eastern Washington and tour wineries on spring break and weekends. Making wine was the same thing as chemical engineering. There are reaction chambers. There are valves and pumps.”

WTO protests spark new career

Life for Primus seems to be about taking a path all his own. He pronounces his last name as premise, which differs from how family elders say the surname. Political activism found the chemical engineering student on the streets of Seattle for the World Trade Organization conference, and what he witnessed Nov. 30, 1999, changed his life.

“I was there mostly for the GMO aspect of the protests, but I began to see that these people around me protesting were the most creative and inventive people I had ever been around,” Primus said. “Now I had been in academic chemical engineering, and those are widely considered to be some of the most intelligent people in academia. It was then I decided it wasn’t just a dream to go make wine. That was something that I could do.”

Winemaking career began at Columbia in Woodinville

He cut graduate school short, but not until receiving his master’s, and began working in Woodinville at Columbia Winery for David Lake — the region’s first Master of Wine — and biochemist Bruce Watson.

“They had an opening in the cellar, but it was for $10 an hour and for someone who could take instruction in English and show up for work on time,” Primus said. “Bruce really recommended that I go to SupremeCorq in Kent, Wash., making synthetic cork. He said that would be a much better use of my education and make me more money.”

That would have meant working with plastics. Instead, he got a level of training that few at any level of winemaking receive.

“Every six months, they would pull out all of their previous vintages of wines and do scientific measurements of them,” Primus said. “All their Cabernet Franc going back 20 years. All the Peninsula wines. Every Cabernet Sauvignon. Every vineyard designate. Being part of the production crew, I got to taste through all those wines and learn about weather conditions and how the processing changed over time. That’s an education you cannot pay for.”

He spent a year working in the cellar at Columbia, then he was ready for the next phase.

“I was encouraged to live where the grapes are grown, and we had some friends who were living in Portland and wanted us to live down there,” Primus said. “So we moved there, and I started working for vineyards and wineries in the Willamette Valley making Pinot Noir, Riesling, Pinot Gris, Chardonnay.”

Willamette Valley took him to Ponzi, Brooks, Adelsheim

He worked in Dundee at the Ponzi Wine Bar and at wineries such as Maysara, J Christopher, Brooks and Adelsheim for the likes of Jay Somers, Jimi Brooks and David Paige.

“I was working for places that were small enough that they needed someone in the vineyard as well as someone in the winery, and with my academic background, they really valued my analytic skills in the lab and my work ethic,” Primus said.

He and his childhood sweetheart, Darla Jungmeyer, enjoyed living in the Willamette Valley, but they returned to their home state of Missouri, where they hoped to plant vines on limestone soils and launch a family winery. Alas, the plan unraveled quickly.

San Juan Vineyards founder dies in 2006

At the same time, San Juan Vineyards was reeling.

It was the spring of 2006 and Yvonne Swanberg, who manages and co-owns the winery, just watched her husband, Steve, lose a two-year battle with prostate cancer. Their winemaker, Dave Harvey, gave notice. Crush for the 4,000-case winery was around the corner, and Swanberg needed a replacement because neither she nor winery co-owner Tim Judkins — her husband’s business partner and motorcycle buddy — had the ability or desire to make wine.

Primus had both, and he wanted to return to the Pacific Northwest.

“I was looking for a job on winejobs.com, and Yvonne was looking for a winemaker and someone to take care of the vineyard,” he said.

Primus beat out 40 applicants for the job and arrived just as harvest was about to begin — two months after the funeral.

Eight years later, she says, “I am fortunate to have Chris for a winemaker.”

Anyone not born on the island tends to be viewed as an outsider to some degree, so life on San Juan Island isn’t for everyone. And it’s not easy for winemakers working with Puget Sound vines and relying on the ferry system to transport the red grapes in a timely manner from the Columbia Valley.

“Logistics are definitely an issue,” Primus said. “There is a problem with getting supplies for winemaking, and there are not really resources on the island to repair your tractor or your forklift if they break down.

“People told me repeatedly, ‘If you are going to use it, you need to know how to work on it.’ So I’ve become very adept at working on all the equipment we have here and making things work,” he continued. “It’s taken a few years to build up my collection of replacement parts, but I’m fairly self-sustaining out here.”

5 acres of Madeleine Angevine, Siegerrebe vines

There are also the 5.1 acres of vineyards. Primus manages 2.9 acres of Madeleine Angevine — a Loire Valley cross of Madeleine Royale and Précoce de Malingre — and 2.2 acres of Siegerrebe, which is a cross of Madeleine Angevine and Gewürztraminer. They were planted by the Swanbergs in 1996 and 1998, and it’s difficult to tell which variety Primus prizes the most.

“To me, Madeleine Angevine is really a food wine,” he said. “It’s nice, high acid and the fruit isn’t too forward. It’s restrained but beautifully aromatic with a nice texture in the mouth. It’s just a very complete wine.”

Those who enjoy a drier style of Gewürztraminer should consider reaching for a Siegerrebe from the Puget Sound. His 2012 vintage earned a gold at last year’s Riverside International Wine Competition.

“I think of it as being a muted Gewürz,” Primus said. “It’s not as rich or musky, a little bit leaner, but still a very sensual wine that’s very expressive of itself.”

Primus embraced his move to San Juan Vineyards in part because of a deep-seated love for aromatic whites wines. The infatuation began in France where he met up with a college friend who had winemaking and grape growing relatives in the Alsace.

“We were there in 1996, and they were pouring us ’89 Rieslings most of the time we were there and serving food that was just amazing because they went with the wines incredibly well,” Primus said. “I hadn’t been exposed to that aspect of the wines I was buying locally (in the United States). I wondered, ‘Why aren’t these the most popular wines in the world? Why are they not the most expensive wines in the world?’ They are very aromatic, complex and they go incredibly well with food. That fit all the bills that I thought wine should meet. So I became a fanatic about those white wines.”

San Juan Vineyards also makes a vineyard-designate dry Riesling from Les Vignes de Marcoux, thanks to Primus’ relationship with Lake’s longtime friend — Mike Sauer of famed Red Willow Vineyard in the Yakima Valley.

Sour rot wipes out Madeleine Angevine in 2013

This winter, the stainless steel tank that’s reserved every year for Madeleine Angevine sits empty. Sadly, Primus lost his entire 2013 crop of Madeleine Angevine to sour rot. Fortunately, it didn’t affect the Siegerrebe. And last year was the first time Primus didn’t concern himself with Pinot Noir.

“It was planted in 1998, and we tore it out in the spring of 2013,” Primus said. “It that time — in 15 years — there had been one harvest that successfully made it into a commercial bottling. That was the very hot vintage of 2009. It’s just too cool here. We have a very long growing season. The spring frost is very early. The fall frost is very late, but the temperatures during the growing season are too mild.”

Workers don’t warm up to the thought of maintaining vines in the San Juan Islands, either.

“Folks in the summer get paid $20 an hour to work on landscape crews to run weed eaters and lawn mowers,” Primus said. “People get $25 an hour to clean houses and vacation rentals, so getting people to work in your vineyard for less than $20 an hour in the summer becomes a challenge because it’s back-breaking labor.”

Outdoors adds to charm of San Juan Island

Outdoor activities make San Juan Island a destination for tourists and a lure to those who hope to carve out a living while pursuing their dreams as kayakers, boaters and cyclists. An estimated 40 percent of the homes on the island are used merely as recreational property, which can make it especially difficult on merchants and restaurants during the shoulder and winter seasons.

“Cycling on the island is world-class, and the temperatures year-round are really nice,” Primus said. “I commute to work year-round by bike, except during harvest. I have the intent to ride during harvest, but it becomes too overwhelming.

“I also like to TRY to play guitar,” he continued. “I’m certainly not a master of it, but it’s relaxing and it forces me to use the other part of my brain. We also love to cook and use the locally raised vegetables and locally raised animals for meat. I wish I could get into sea-kayaking, but there’s just so much other stuff.”

San Juan Vineyards up for sale

Part of Primus would seem content to continue as an island winemaker. In the winery on Roach Harbor Road, he listens to scores of cassette tapes that feature Bob Dylan bootleg recordings in addition to a kaleidoscope of other music he’s discovered in closeout bins. But there’s also a pull to return to the Willamette Valley. He misses working with Pinot Noir.

At the same time, San Juan Vineyards has been shrouded by an uncertain future from the day Primus first arrived.

Swanberg has been trying to arrange for new ownership since her husband died, and she seems optimistic the winery will be sold this year. She left Spokane and moved to San Juan Island with Steve in 1979 to launch their insurance business. Planting vines and operating a winery were his hobbies, so after running the winery for more than seven years without him, she’s ready to retire and return to Spokane. That’s where her family is.

“My dream is that San Juan Vineyards sells to someone who has a passion to take it to a new level,” Swanberg said. “There are so many things that can happen on the property to make someone’s dreams come true.”

Leave a Reply