LOPEZ ISLAND, Wash. — Brent Charnley has called Lopez Island his home since the summers he spent living in a teepee with his parents. And the rare times when he has left Washington’s San Juan archipelago for long, the reason often involved wine.

Early on, it was kismet. Now, he’s into his fourth decade as a winemaker, a career that began with a trailblazing double major at the University of California-Davis. And Charnley has found not only a way to create world-class wines in the Puget Sound with two obscure grape varieties, but he’s also farmed them under certified organic standards at Lopez Island Vineyard & Winery since 1989 — making him perhaps the first in the state to do so.

“I’d like to see more people doing it,” Charnley told Great Northwest Wine. “I don’t need to be first on that. I’d just like to be included in the conversation because it is unique. And I’d like to be remembered for being there early on, but we do feel a little more vindicated as time goes on and as more vineyards are becoming certified.”

Thoughtful, well-spoken and yet soft-spoken, Charnley takes a practical and wholesome approach to farming and winemaking on the edge of viticulture viability and in the middle of the Salish Sea. He and his wife, Maggie Nilan, have done things their way — naturally — thanks in large part to their island community. And they’ve staked their claim with two fascinating grapes, fun varieties known primarily by wine geeks who appreciate the subtleties and seafood-friendly profiles.

Siegerrebe, Madeleine Angevine fun to say, easy to like

Siegerrebe (pronounced SEE-grr-ray-buh) and Madeleine Angevine (on-jah-VEEN) have been the key to Lopez Island Vineyards’ success, starting soon after their planting at the 6-acre vineyard in 1987. During a good harvest, the two grapes make up about 800 cases of the winery’s annual production of 1,500 cases.

“My introduction to those varieties was with Dr. Robert Norton at WSU Mount Vernon’s research station,” Charnley said. “In the ’70s, he had started an experimental planting with varieties really geared toward home winemaking and maybe thoughts of an industry in the Puget Sound area. This was just when vinifera growing was taking off in eastern Washington.”

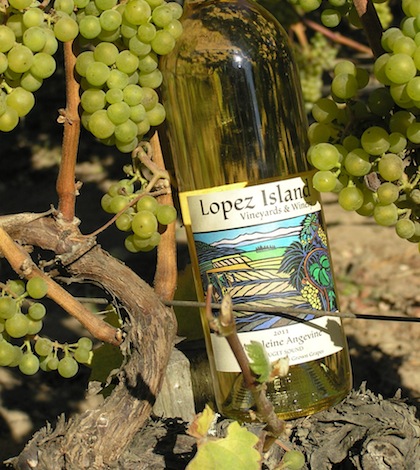

Siegerrebe, which means “victory vine” in German, comes across as the more unctuous grape. Madeleine Angevine would seem to be Charnley’s favorite, not just because it’s a bit more hearty.

“Its parentage comes from two even more obscure grapes from the Loire Valley, and people have told us that Angevine is sort of an indication of where it was probably bred and originally planted,” Charnley said. “In comparing it to Loire wines, we’ve found the closest pairing to Sancerre, which is Sauv Blanc. It’s not grassy like New Zealand Sauvignon Blancs or as full-bodied and viscous as eastern Washington or Bordeaux Sauvignon Blancs. It’s more like the crisp, very citrusy Sauvignon Blanc from the Loire Valley. That’s usually the comparison we make.”

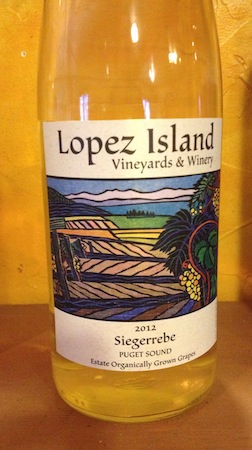

Lopez Islands’ 2012 Siegerrebe earned a Double Platinum last year from Wine Press Northwest’s 14th annual Platinum Judging of the “best of the best.” There were 180 cases produced.

“With Siegerrebe, which is a German cross of Madeleine Angevine with Gewürztraminer, it’s an easier comparison to make with a known varietal,” Charnley said. “I think it’s got a lot of the similar characteristics of Gewürztraminer. You’ve got the very distinct lychee fruit. You can even pick up clove and banana spice in it, depending upon the vintage, however it also has a very strong pink grapefruit and citrus quality that I think is coming from the Madeleine.

“Comparing it to Gewürztraminer, at least in this country, is sort of a weighting comparison because most Americans associate Gewürztraminer with very sweet wine,” Charnley continued. “It’s an unfortunate comparison because dry Gewürz from this state and the Alsace region are a much closer comparison to our Siegerrebe, which has a little bit of residual sugar, although it’s usually less than 1 percent.”

Charnley consistently earns high scores with his aromatic Siegerrebe, but he’s more enchanted with his Madeleine Angevine, a cross of Madeleine Royale and Précoce de Malingre that began to gain a substantial foothold in England in 1984, according to famed British writer Jancis Robinson.

And while Charnley has gained a following for it with seafood restaurants and organic-minded grocers in the Puget Sound, he’s befuddled that his Madeleine Angevine doesn’t fare better in the annual Pacific Coast Oyster Wine Competition — a 20-year-old event that stages its championship round in Seattle. He believes so much in the variety that he has nicknamed it “Siren of the Sea” and gives it a bit more attention with neutral oak fermentation to gently file down a bit of its edge.

“I think Madeleine Angevine has ended up being the brilliant crisp white that we associate with some of the wines in France that go with oysters and other delicate seafoods,” Charnley said. “For us, it’s been a natural pairing through the years. We continue to enter it almost every year, but it has not been in that final selection of 10 to 20 oyster wines. We frankly don’t get it. We think it’s a great combination.”

Last month, Lopez Island Vineyards & Winery released its 2012 Madeleine Angevine ($25), which received an “Outstanding!” from Great Northwest Wine. Production was 245 cases.

Natural path led, binds Charnley to San Juan County

“Lopez Island was part of my growing up since I was born,” he said. “I was born in May and I think my parents bought a small parcel on San Juan Island that very day, so we would camp out there at Roche Harbor and we did that for six or seven years.

“My father also had gone to a children’s camp called Henderson Camp, and that was on Wescott Bay, where the Wescott Bay oyster farm is now. When he was a youngster, it moved to Lopez Island’s Sperry Peninsula. He worked at that camp and helped establish it in the ’40s and ’50s, so part of my childhood we would live in a teepee at the camp while he was working there. So Lopez Island very early became home for me.”

At first, he didn’t stray far for his college education, attending what is now Western Washington University where he studied studio arts. There was no culture of wine consumption in his family, but he began to dabble in winemaking while in Bellingham.

At first, he didn’t stray far for his college education, attending what is now Western Washington University where he studied studio arts. There was no culture of wine consumption in his family, but he began to dabble in winemaking while in Bellingham.

“There was a little wine/art store in town, and I bought a kit and the very first wine I made was dandelion wine. It wasn’t very good,” he chuckled. “The second one I made was Himalayan blackberry, and it actually turned out pretty nice.”

His epiphany came during a trip to Europe in 1979, toward the end of his time at WWU.

“I was hitchhiking around and serendipitously came across an apprenticeship in the Bordeaux region in France, so I spent a full growing season on a vineyard there,” Charnley said. “We were growing primarily Merlot and Cab Franc just east of Saint-Émilion. That brought grape-growing as a strong interest and passion of mine, and that was when the dream of coming to Lopez with grapes someday first coalesced.”

The maritime climate of the San Juans make it impossible to grow the red grapes of famed Chateau Cheval Blanc, but Charnley was determined to find a way to create an estate vineyard and winery on Lopez Island.

“There were two ways to go at it — one would be to get an apprenticeship particularly with a winemaking aspect, and the other would be to go to school,” he said. “So I cast about and found a program at U-C Davis and was accepted there.

“I enrolled in 1980, just after I got back from France, and completed one of the first combined majors of viticulture and enology at Davis,” he continued. “There were just two of us pursuing that. At the time in the wine industry, you did one or the other. The departments were very separate, and they were on different floors, as I recall.”

His enology adviser was acclaimed biochemist Ralph Kunkee, who died in 2011. Charnley fondly remembers the avuncular professor and felt comfortable knowing the faculty supported the Washingtonian’s novel bid to study two majors at the same time.

“The reason I did that is I saw myself at a smaller operation where I would be doing both aspects,” Charnley said. “I love being outside, and one of my favorite jobs is pruning in the wintertime. And the artistry of making the wine goes back to what I was studying before I got into the wine, which was fine arts.

“It is remarkable, isn’t it?” he added rhetorically.

Growing close to home

While on his final winter break from Davis, Charnley found himself back at WSU’s extension office in Mount Vernon because the staff asked him to share some of his pruning teachings. It also afforded him a closer look at some of the varieties he was considering for his own vineyard someday. Those pruning clinics he staged also helped him land him a position near Bellingham.

“Dr. Norton was getting some of his varieties and advice from Gerard Bentryn, who had been working in Germany and was really looking for cool-climate varieties himself for his vineyard on Bainbridge Island,” Charnley said. “The winemaker for that program was Dr. Al Stratton, who founded Mount Baker Vineyards in 1980.

“I had three different job offers out of UC-Davis — one I wish I had done was working with David Lake at Columbia Winery — but I chose Mount Baker Vineyards because they had 30 different grape varieties in their vineyards. My hope was that something there would grow on Lopez because it was fairly cool.”

When Mount Baker Vineyards began, it boasted nearly 50 varieties, and Charnley took over the winemaking at the new Everson winery soon after he graduated Davis with his bachelor’s degree in viticulture and enology. He made the wines at Mount Baker for three years while he and Maggie laid the groundwork for their own winery on Lopez, where they had established two test sites. One of those blocks ended up becoming the home for his present-day winery.

“Madeleine Angevine, Müller-Thurgau and Madeleine Sylvaner were the three I had planted on this site,” Charnley said. “On my other test plot at the south end of the island, I had Gray Riesling and some stuff I had brought back from the certified block at Davis.

“Really, they were certified,” Charnley quickly added with a chuckle. “But the experience at Mount Baker and my stumbling across a few Siegerrebe plants in their experimental row really cemented for me that those were the varieties to try out there (in the islands).”

It’s interesting to note that 35 years after those first plantings, Mount Baker Vineyards now produces estate wines from just six varieties — Chasselas, Madeleine Angevine, Müller-Thurgau, Pinot Gris, Pinot Noir and Siegerrebe.

And global climate change has not necessarily made viticulture easier at Lopez Island Vineyards.

“We have had some cold springs for the last 10 years, making for delayed harvest, and 2010 was our roughest vintage,” Charnley said. “We harvested nothing that year due to no fruit set on Siegerrebe (a cold spring) and rain on the Madeleine, which was worse than 2013.”

70 shareholders critical to start of Lopez Island Winery

By 1987, Charnley was geared up to start Lopez Island Vineyards, but not the winery. He’d entered into a lease with a friend for his first 2 acres of vines. Support of his neighbors remains critical to the success of the winery, and Charnley developed a stock program in 1990 that led to 70 shareholders whose capital allowed Lopez Island Vineyards to get its first commercial wines into bottle.

“In a sense, they helped us get off the ground. They’d come out early on, and they’d help us pick. A lot of them still do,“ Charnley said. “They are good customers and good rallying support.

“At the time, we felt they were doing it to be part of a company and make some money, but as we learned they really got involved because they were really behind what we were doing, either because of an interest in wine or that we were actually using and preserving farmland on the island — which was disappearing and continues to.

“They wanted to see a small business that was providing jobs on the island,” he added. “They’ve gotten that return on their investment, and they are pretty happy about that.”

Organic vineyard fits with island farming at LIV

Charnley does venture off the island and into the Columbia Valley for his red wine program, but there’s no doubt Lopez Island Vineyard & Winery receives regional support in part for his organic farming practices the state certified in 1989. Badger Mountain Vineyard, an 80-acre planting in Kennewick, was certified organic by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 1990.

“We’ve been doing it for the full 27 or 28 years we’ve been at it,” Charnley said. “The back-to-the-land movement here on the island was in full swing, and they were trying organic farming. The vineyard I worked at in France, while not certified, was farmed organically as well, so it was easy to pick up from that experience.”

Organic practices were not widely embraced at Davis while he studied there, Charnley noted.

“It was difficult to study that at Davis because it was the source of all the miraculous innovations in agriculture — and particularly chemical-based agriculture,” he said. “In the early ’80s, there were a few young professors who were researching organics, but they were by and large in the minority, and the old guard was a little defensive of their work.

“I got laughed at when I asked questions about organic farming, even by my peers in school, so it’s sort of a nice turnaround that people have come around, but it was uphill struggle for a while,” Charnley continued. “I feel for a long time it didn’t make a difference. People weren’t looking for organics in wine, and it’s still a minor part of the market. It does help now, and people are always thanking us and saying that it’s a bonus that it’s organically grown.”

Support of a local business comes into play when the weather warms up and Charnley opens up his young tasting room at Lopez Village, and there are a few events still staged at the winery gardens, but the organic approach plays strongly at farmers markets and store shelves in the Seattle area.

During the winter, Lopez Island wines are poured as part of a regular rotation with a handful of other wineries and cider producers. And PCC Natural Markets continues its long-term support Charnley’s organically grown wines — the Madeleine Angevine and Siegerrebe — and the blackberry wine he makes using Lopez Island berries.

Salvaged driftwood turns into long-lasting vineyard posts

From the start, Charnley and his wife used a light hand across their own property, primarily because they couldn’t afford to be irresponsible, wasteful or harmful.

“Maggie and I really had very little money. We had around $14,000, and that basically bought a tractor, a tiller and some deer fencing, so we got started just by bootstrapping. We scrounged our cedar posts for the fencing and the posting — and all the stakes for the vines — from the beaches here on the island. So it’s old-growth cedar salvaged from the island, which is fairly long-lasting in this soil.”

There’s scant newfangled equipment in the 34-year-old winery, and Charnley continues to do much of the vineyard work by hand, which he seems to honestly embrace. That’s good because it’s neither easy nor cheap to hire professional help on the San Juans during harvest, and his five children have created lives for themselves beyond the island and around the world.

There’s scant newfangled equipment in the 34-year-old winery, and Charnley continues to do much of the vineyard work by hand, which he seems to honestly embrace. That’s good because it’s neither easy nor cheap to hire professional help on the San Juans during harvest, and his five children have created lives for themselves beyond the island and around the world.

At this point, Charnley, 56, has no succession plan in place, although it’s difficult to imagine what Lopez Island Vineyards & Winery would look like without his approach to farming, his winemaking and his deep ties to the islands.

“We’ve had a lot of help through the years,” he said. “Initially from friends and shareholders and of course my wife, Maggie, who spent years out there with me with the pruners and hoe, and our kids as they have grown up also have been a big help.

“But none of this would exist just by my own force of will, that’s for sure. It’s because of these connections and a community’s effort that we’re here.”

Leave a Reply