PROSSER, Wash. – More than 30 years after it was created, the Columbia Valley American Viticultural Area continues to define the Washington wine industry – even as it has been further refined with the additions of smaller AVAs within it.

Wade Wolfe, owner and winemaker of Thurston Wolfe Winery in this Yakima Valley town, was instrumental in defining the Columbia Valley, working directly with Walter Clore in the early 1980s.

Wolfe arrived in Washington in 1978 as a viticulturist for Chateau Ste. Michelle, and the first person he worked with was Clore, hailed as “the father of Washington wine,” had retired from Washington State University two years before and became a consultant for Ste. Michelle.

We recently sat down with Wolfe to talk about the formation of the Columbia Valley AVA and how important it has remained to the Washington wine industry. Here’s the interview:

[powerpress]

Please take a moment to click and leave an honest rating or review in the iTunes Store. It will help others learn about the wines of the Pacific Northwest.

Creating the Columbia Valley

Wolfe and Clore were tasked by Ste. Michelle chief Allen Shoup, who wanted a tool to help the Washington wine industry move forward.

“His concern was that as Ste. Michelle was getting out into the national marketplace, there was confusion about ‘the other Washington,’ especially when you’re working on the East Coast and people’s lack of knowledge of the wine industry in Washington,” Wolfe told Great Northwest Wine. “So he felt that it was important to come up with a specific AVA that identified the interior area of Washington state as a premier wine-growing area. He felt it was necessary to create an AVA to help promote not only Ste. Michelle, but also Washington wines in general.”

At the time, the Washington wine industry consisted of only a few thousand acres of wine grapes and perhaps three-dozen wineries. Defining the Columbia Valley was no simple task, Wolfe said.

“We finally came up with the idea that we would do an elevation boundary,” Wolfe said. “We chose approximately 2,000 feet because above that, we didn’t think it was practical to grow grapes, either due to lack of water or due to insufficient heat units. So we did an initial boundary that way.

The Yakima Valley was approved in 1983, the year before the Columbia Valley. Wolfe and Clore started with the western border of the Yakima Valley as a starting point, then went north, roughly following the Columbia River. To the west, the elevation in the foothills of the Cascade Mountains rapidly rose to 2,000 feet. The northern border went from Lake Chelan east toward Spokane.

This is where the boundaries became murky.

“One of the biggest challenges was trying to come up with the east boundary,” Wolfe said. “As soon as you get south of Spokane, you start getting into the Palouse wheat-growing area, and we felt that we would have to remove a large percentage of that due to a combination of issues with 2,4-D (an herbicide used by wheat growers) being incompatible with grapes and a lack of irrigation water in the area.”

South of the Palouse, Wolfe and Clore used the Snake River as the eastern border, leaving Clarkston, Wash., in the Columbia Valley but nearby Lewiston, Idaho, out of it.

Columbia Valley becomes bi-state AVA

The next big controversy was the southern border. Originally, the pair used the Columbia River, which separates Washington and Oregon. That would have kept the Columbia Valley entirely within Washington.

“But during the comment period, we got a lot of pushback from a number of people in the Oregon industry saying (the Columbia River) was an artificial boundary, that the northern part of of Eastern Oregon should be included, too, because basically the climate and soils are identical or very close,” Wolfe said.

So the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms – which regulated the American wine industry prior to the Sept. 11, 2001, terrorist attacks – came to Wolfe and Clore and said a section of Oregon needed to be included in the Columbia Valley.

Already, the Walla Walla Valley was a bi-state AVA, so the Columbia Valley followed suit.

In 1984, the Columbia Valley became Washington’s third AVA, following the Yakima Valley in 1983 and the Walla Walla Valley earlier in 1984. It is more than 11 million acres in size, taking up nearly a third of the state. Today, more than 50,000 acres of wine grapes are being grown in the Columbia Valley, and only two of Washington’s 13 AVAs are not within the Columbia Valley’s borders.

More than any other Washington AVA, the Columbia Valley appears on the labels of Washington wines.

Clore’s role essential to defining Columbia Valley

Clore arrived in Washington from Oklahoma about the same time that Prohibition was repealed at a national level in 1933. He was an agricultural researcher at Washington State College (later WSU) in Pullman, and he moved to the Yakima Valley town of Prosser in 1937 to work at the university’s irrigation research station there. Clore lived there for the rest of his life – he died in 2003 – and left an indelible mark on the Washington wine industry.

By the time Wolfe arrived in 1978, Clore already was retired from WSU and working for Ste. Michelle. And he already was a legend in the wine industry, which he’d worked in and around for decades.

“He pretty much was my mentor and took me around and introduced me to all the growers and the different growing areas and explained to me what he felt were the pros and cons of existing vineyards and where he thought there was potential for additional ones,” Wolfe said. “He was a great gentleman, really easy to get along with.”

Yet Clore also brought his scientific approach to the task of defining the Columbia Valley, Wolfe said, putting together detailed information about climate, soil types, temperatures and the history of the region.

Shoup, who retired from Ste. Michelle in 2000 and went on to launch Long Shadows Vintners in Walla Walla, told Great Northwest Wine that it was Clore who came up with the name “Columbia Valley.” Most maps and resources referred to the region as the “Columbia Basin,” which the team and Chateau Ste. Michelle believed was an unmarketable name. But Clore managed to track down a reference to “Columbia Valley” made by none other than Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the two intrepid explorers who came through the region in the early 1800s on their trek to the Pacific Coast.

New AVAs subdivide Columbia Valley

Today, Washington has 13 AVAs – and a 14th is likely to be approved as early as this winter. Of these, only two are not inside the Columbia Valley: the Puget Sound AVA (approved in 1995) and the Columbia Gorge (another bi-state AVA that was approved in 2004).

Until 2001, the Columbia Valley surrounded the Yakima and Walla Walla valley AVAs – both of which were approved prior to the Columbia Valley. But in 2001, Red Mountain became an official AVA, and it was contained within both the Columbia and Yakima valleys. Since then, several sub-AVAs of the Columbia Valley have been formed. They include:

- Horse Heaven Hills (2005)

- Wahluke Slope (2006)

- Rattlesnake Hills (2006)

- Snipes Mountain (2009)

- Lake Chelan (2009)

- Naches Heights (2011)

- Ancient Lakes of Columbia Valley (2012)

All of these child AVAs build upon the original work of Wolfe and Clore – and none of that bothers Wolfe one bit. He said the work of defining smaller AVAs have become a bit easier because “we have a lot more information about the grape performance and soils and climates,” he said. “(The Columbia Valley) is still the all-encompassing AVA that really defines – at least as far as we know now – the potential wine-growing areas of Eastern Washington.”

Anyone who thinks Washington has too many AVAs need only look at California’s most famous region: Napa Valley. Though only 30 miles long and three miles wide – much smaller than the Yakima Valley – Napa Valley is divided in 16 separate AVAs. Across the mountains to the west, Sonoma County has an additional 16 AVAs.

Overall, California has about 120 AVAs.

No regrets about Columbia Valley

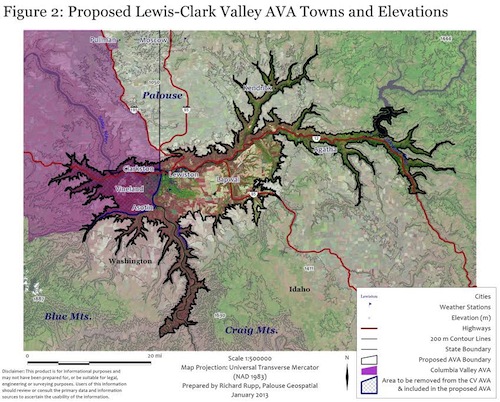

What will undoubtedly be Washington’s next AVA is the Lewis-Clark Valley, a bi-state AVA that will be shared with Idaho. It is surrounded by a bit of controversy because the petition calls for about 57,000 acres of the Columbia Valley to be resected. This is because the federal government doesn’t want the Lewis-Clark Valley to be partly within the Columbia Valley and partly outside of it.

The solution is reduce the size of the Columbia Valley by less than 1 percent, a concept that doesn’t concern Wolfe in the least.

“I’m always open to something that makes more sense,” Wolfe said.

He said that when he and Clore were researching the proposed Columbia Valley AVA in the late 1970s and early 1980s, they never considered crossing into Idaho and instead made the Snake River the eastern boundary.

“I don’t remember a specific discussion on that boundary. When we did the Columbia Valley, (the federal government) seemed to emphasize river drainages as the logical basis for drawing boundaries,” he said. “That was the criteria. As we’ve gotten into smaller AVAs, there’s different criteria for those boundaries. They seem to be using elevation and the relationship to geology and soils that are formed within an area.”

Wolfe said he was among those suggesting the Columbia Valley be reduced in size so that the Lewis-Clark Valley would not partly overlap with the Columbia Valley.

“Ultimately, I’m a pragmatist,” he said. “I think it’s totally reasonable to make those kinds of modifications.”

But aside from that, Wolfe can look back on the work he and Clore performed more than 30 years ago and remain satisfied.

“I don’t think I would do a lot differently,” he said. “With the new AVAs all being within (the Columbia Valley), I think it adds legitimacy to that original concept.”

The map that Wade and Walt brought to me drawn by Lewis and Clark was not just any map… it was a map they sent back to Thomas Jefferson with a letter and it mapped the entire NW. The map is quite famous and easy to find… it should be used more in the telling of the WA wine story as it clearly demonstartes our most unique (and possibly our most important viticulture feature) it shows a vast valley of land that rest between the western mountians of Idaho and the Cacade range in WA. It drifts down into Oregon and its distinguishing feature is that it had no trees …just praire and high desert. A area we now know was created by the great Missoula Floods that date back 10,000 to 20,000 years ago during the last Ice Age (now known to be the greatest floods ever documented by man). Our great wine story stems from this beginning as almost 100% of WA wine vines are a product of these floods plains.