PORTLAND — The Pacific Northwest wine industry is brimming with success stories, and Ken Wright continues to write new chapters.

Earlier this month, the iconic Oregon winemaker shared a few pages of his history to help celebrate the rebirth of Panther Creek Cellars — the brand he launched in 1986 upon his arrival to the Willamette Valley.

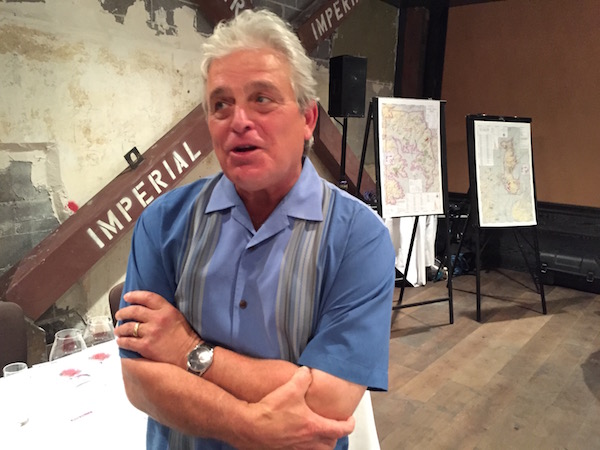

“It was not an easy road at all,” Wright told a gathering of trade and media at Imperial in downtown Portland.

Bacchus Capital Management two years ago entered partnerships with DeLille Cellars in Woodinville, Wash., and Dobbes Family Estate in Dundee, Ore., to help those renowned brands take the next step in their growth. However, Bacchus itself owns and operates Panther Creek after purchasing the winery in 2013 from the Chambers family — owners of Silvan Ridge Winery in Eugene, Ore.

Soon after, Bacchus hired Tony Rynders to make the wines for Panther Creek, which now has a tasting room in Dundee. To celebrate, Bacchus reunited Wright with two of his favorite people in the Willamette Valley wine industry — Rynders and renowned Imperial proprietor/chef Vitaly Paley — to unveil several new releases by Panther Creek, including its 2013 Carter Vineyard Pinot Noir.

Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part series on the progression of Panther Creek Cellars.

Rynders adds Panther Creek to project list

“It seems habit-forming, but I’ll take the handoff from you,” Rynders told Wright, the longtime manager of Carter Vineyard.

Rynders, pronounced RHINE-ders, continues to operate his own brand, Tendril Wine Cellars, and serve as consulting winemaker for a number of projects, including Saffron Fields. He first arrived in the Pacific Northwest as an assistant winemaker at Argyle Winery in 1994.

“Tony was a friend long before we did anything winemaking-wise when he was at Argyle, and then he took over at Domaine Serene when I could no longer keep up with that,” Wright said. “Domaine Serene was only going to be 1,000 cases a year. It became much different than that,” Wright said with a laugh after shooting a glance at Rynders. “In 1998, Tony came on to take over, and he and I worked together for about five months. It was a pure joy for me. He did a remarkable job there, over about a decade.

“So here we are, and Tony approached me a couple of years ago and said, ‘You know, I’d really love to do something — now that I’m associated with Panther Creek — with one of your foundation vineyards,” Wright said.

Wright showcases 20-year-old wines from Carter

Wright, 61, added some historical perspective by pouring two wines he crafted from Carter Vineyard decades ago, a 1993 he made for Domaine Serene and a 1994 under Ken Wright Cellars. The brilliance of both library wines, particularly the Domaine Serene — which could have passed for a 2013 — would have made it difficult to focus on a speaker less charismatic than Wright.

The latest proof of his role on the global wine scene recently appeared on newsstands as Wright served as the cover story for the May 2015 issue of Wine Spectator.

Editor-at-large Harvey Steiman wrote that profile, but Wright skillfully tells his own story, too. In some ways, the opening chapter begins with Allen Holstein, the first vineyard manager for Knudsen Vineyards whose influence and work continues to live in vines at Argyle, Domaine Drouhin Oregon, The Eyrie Vineyards and Stoller Family Estate.

“Allen and I were high school friends in Kentucky, and we planted the first vineyard at the University of Kentucky, which was a disaster,” Wright said. “There are horrible diseases in Kentucky that we don’t have here because of humidity levels — things like black rot, disgusting things — and the chemicals you would need to use to prevent disease are worse than the disease.”

They took separate paths after graduating from UK, with Holstein heading to Oregon State University, while Wright matriculated to University of California-Davis.

“We visited quite often, though, and he would come down from Oregon bring some beautiful wines to try, and I visited him quite often,” Wright said.

Visits to Oregon started 40 years ago

Wright’s trips to Oregon began in 1975, which he looks back on as “riveting experiences.”

The wines spoke to him in terms of “pure, fresh fruit. Spot-on fruit. Not dried fruit. Not green fruit. Just spot-on. That’s where I wanted to be, but I couldn’t afford to make that happen at that time. I didn’t have the dollars.”

His influences include many of California’s historic figures, Chalone founder Dick Graff, Larry Brooks, Steve Kistler, Ric Forman, Josh Jensen, Steve Doerner, Rich Sanford and Bruno D’Alfonso.

“Being in that group was a marvelous experience for me,” said Wright, whose junior status meant handling the duties as the group’s secretary. “I was the kid in the group who knew nothing.”

In the meantime, he planted vines and made wine in California’s Central Coast, first for Ventana Vineyards and then in Carmel Valley for Talbott Vineyards, whose family first became famous for luxury neckties. They struck a deal early on with Wright as he helped developed the wine business, which started in 1982.

“When the son, Robert, who was my age, was ready to take over, they would value the company, and I would be paid a percentage of the way I left that company,” Wright said. “That check is what started me here in Oregon.”

Wright uses California Cab to launch Oregon winery

Those first wines, and how they came to be sold in Oregon, is the stuff of lore. And it started with 10 barrels of wine from the vines of Martin Ray, one of the forefather’s of the modern California wine industry. Martin’s widow, Eleanor, a best-selling author born in Yakima, Wash., asked Wright to buy her Mount Eden fruit from the 1986 vintage. It was another instance when the next generation — in this case, Ray’s children — wasn’t quite ready to step in. And Wright made that wine at Talbott.

“The kids were too young to take over,” Wright said. “I took all the fruit — 10 barrels of Cabernet Sauvignon and Merlot — and when I moved up here, those 10 barrels came with me. In the van.”

He set up shop near the railroad tracks in McMinnville, Ore., and using a former Carnation milk building — a model of gentrification that he’s since applied to downtown Carlton. However, Wright somehow overlooked the fact that he transported bonded wine from California to a facility without a bond for wine.

“I was just naive,” he said.

At that point, his future as a winemaker in Oregon rested in the hands of federal agent Ron Fitzgerald, who arrived to interview Wright.

“This is when they used to come see you before you could be a winery,” Wright said. “They don’t do that anymore.”

Fitzgerald went through his checklist and noticed Wright already had barrels.

“I said, ‘Yeah, I’ve got some great wine from Mount Eden,’ and he goes, ‘What?’ ” Wright said.

Fitzgerald informed Wright that the wine was illegal.

“He said, ‘You are not going to be able to sell that wine. It’s not going to happen,’ ” Wright remembers.

Wright’s reply was, “If that’s true, then I’m out of business before I started. I have to sell that wine.”

Fortunately for the Oregon wine industry, Wright said Fitzgerald “took pity on me. … He ended up writing to all his supervisors asking for forgiveness for me — the idiot.”

And so he launched Panther Creek Cellars via the sales of wine made from Bordeaux varieties, not the single-vineyard Pinot Noirs he’s become famous for.

The influence of Nick’s Italian Cafe

During this era, Wright had no financial margin for error. To make ends meet, he was making wine for not only his business and others, but also waiting tables at night. It was a schedule he kept for five years.

“If you are willing to do that — to sacrifice — good things happen,” he said.

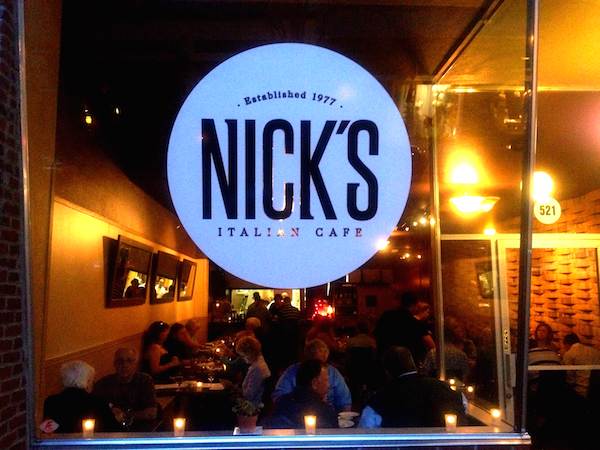

That diligence, talent and charisma immediately endeared him to acclaimed McMinnville restaurateur Nick Peirano of Nick’s Italian Café.

“We did a dinner and we only had the one wine, so we poured the same wine for six courses,” Wright said with a smile. “It was a rocky start for Panther Creek.”

Upon arriving in the Willamette Valley, Wright and his first wife, Chicago writer Corby Stonebraker, considered purchasing vineyard property. They explored Panther Creek Road west of Carlton, near the home of Peirano’s mother. That night, they went to Nick’s Italian Cafe and visited with Nick.

“He said, ‘Wow. I kind of like that name,’ “ Wright said. “He knew we didn’t have a name yet for the winery. What’s really bizarre is that the design of the bottle was already in place. When Corby and I were in California, all the coloration — everything but the name — was done. The design sitting on our table. Nick saw it, picked up the bottle, and said, ‘Suddenly, this coloration is totally about Panther Creek. Don’t you think it works as the name?’ So it was Nick Peirano who named the winery.”

Panther Creek’s first employee

Successful winemaking soon turned into sales, and Wright needed help. He convinced Dale West to leave Sunriver in Bend and became the first full-time employee of Panther Creek in 1991. West followed Wright to Domaine Serene and then Ken Wright Cellars, and he’s come full circle by recently returning to work the tasting room at Panther Creek — this time in Dundee.

“He and I did everything,” Wright said. “On late nights in a cold vintage, when our hands are absolutely frozen, still pressing away at 2 or 3 in the morning… We did a lot of good work together.”

West worked for all three of Wright’s brands, with the first transition coming in 1994 when Wright and Salem dentist Steve Lind sold Panther Creek after a five-year partnership.

“He promised to be a limited silent partner and really was loud,” Wright said. “In the end, in order to move on, we both sold our interests to new ownership. Dale stayed on for a while to help them get on their feet.”

Tasting history of Carter Vineyard

Wright not only related some history of the birth of Panther Creek, but he also shared two stunning examples of Carter Vineyard, a site in the Eola-Amity Hills that’s served as a linchpin of his program.

The Domaine Serene 1993 Carter Vineyard Pinot Noir spent 15 months in 25 percent new French oak barrels, and the listed alcohol by volume of 12 percent.

“We were making Domaine Serene’s wines at Panther Creek for a number of years,” Wright said. “All the fruit that Domaine Serene had at the time, I provided to them from vineyards I worked with. That’s the way it was in the early years before they planted their own. Carter was one of those vineyards.

“’93 was a cooler vintage and it was a fair-sized crop, and it could have been a challenging vintage,” he continued. “In the beginning, the wines had a little bit of an herbal streak to them. It wasn’t vegetal. It was more subtle than that. We were a little concerned that they would not be as opulent as we would like. They were very tight for a long time — not very expressive. However, as is very common now with vintages like that, they bring great reward if you have patience. They have the structure, the acidity to hold. It may take eight to 10 years before there’s enough flesh on the bones. So ’93 — over time — has become quite beautiful.”

Indeed, his 1993 Carter Vineyard for the Evenstads shines with tones of raspberry, boysenberry and Montmorency cherry as red-fruit acidity stays nicely ahead of the tannin structure. There’s virtually no brickishness and no hint of bottle bouquet.

The Ken Wright Cellars 1994 Carter Vineyard, created with similar barrel aging and 12 percent alcohol, seemed more along the line of Marionberry and black currant — darker purple fruit from a riper vintage.

Both wines were made at the historic McMinnville power plant, which Wright turned into a winery in 1990. The city sold him the entire block of property for $100,000. Renovation proved costly and dangerous because of PCBs, Wright said

“We cleaned it all up, I swear,” Wright said, sparking laughter.

1994 vintage key to Oregon’s fame with Pinot Noir

Both the plant and McMinnville became famous because of the wines Wright produced there. And the 1994 vintage put Wright and the rest of the state on the map.

“’94 was probably the year that catapulted Oregon into the national spotlight more than any other,” Wright said. “We got a huge amount of praise from Robert Parker and Spectator. A lot. Massive scores. It was a lightning rod for getting Oregon in front of people nationwide.

“It changed everything,” Wright continued. “Back in the day when we first started going to New York or Chicago or Miami trying to sell our wine, it was everything you could do just to get into the door. Nobody cared about Oregon wine. Nobody. That vintage — ’94 — really did turn peoples’ heads. Suddenly, everybody needed an Oregon Pinot Noir on their lists. Everybody. They wanted to have the representation, and it made it a lot easier to market our wines.”

Wright described 1994 as a “super-warm, smaller crop — not as low as ’98, which was ridiculous. It was warm enough leading up to harvest that it was easy to miss the mark (on picking the fruit). And honestly, I think there were a lot of ‘94s that were way over the top. They were very alcoholic. They were jammy. And they are tired now.”

Two decades later, Wright was in a position to share 150 cases worth of Carter Vineyard grapes for Rynders.

“We’ve done that for a couple of years now,” said Wright, who added that he’s formalizing his purchase of the 36-year-old vineyard from Jack and Kathleen Carter. “It’s a pleasure to be here, and I wish you all huge success going forward. It’s good stuff.”

Nice piece of reportage Eric!