Editor’s note: This is the first of a two-part report on the influence of climate change and how it might affect the Washington wine industry.

LOPEZ ISLAND, Wash. – Brent and Maggie Charnley started their small vineyard and award-winning winery on Puget Sound’s Lopez Island in 1987.

They planted slightly more than 5 acres, snuggled in a perfect spot of microclimate. Move a mile in any direction and the soils, temperatures and rainfall wouldn’t make for quality wines at Lopez Island Vineyards.

Those organic vines, among the first in the state, are in their third decade of life, and the Charnleys now are in their 60s. Brent continues to see temperatures creeping up — climate change. Many scientists blame greenhouse gases for global warming.

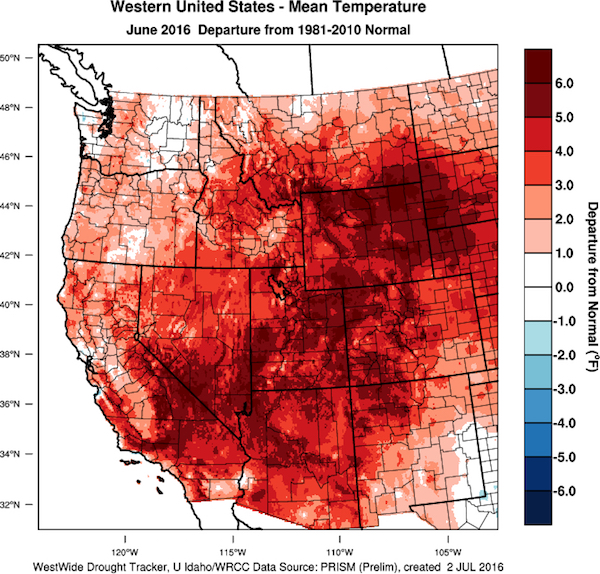

“The last two years have been exceptionally warm,” Charnley said, attributing that to climate change.

So what does climate change and rising temperatures mean to Washington state’s wine industry?

Experts believe the warmer temperatures could lead to significantly more vineyard plantings for wine grapes, especially at higher altitudes. Concord grapes for juice concentrate will likely fade some. Red wine grapes could become more abundant to slake the thirst of consumers. Grapes for less-expensive white wines will make up a smaller percentage.

Irrigators struggle vs. El Niño

During the recent stretch of El Niño conditions in the Pacific Northwest, less snow has been accumulating in the Cascade Mountains. And that snow is melting much earlier than optimal for irrigators and vineyard managers in Eastern Washington, who require timely irrigation to maintain the delicate balance of stressing the vines in order to make the best wine grapes possible.

These changes have already shown up in California’s premium wine regions with that state expecting some shifts on its vineyards there.

Some snapshots help illustrate how climate change and warming is unfolding in Washington state.

- In Clallam County, the average March temperature increased 6.3 degrees from 1960 to 2015, according to the Office of the Washington State Climatologist. The average June temperature for the northern portion of the Olympic Peninsula rose 6.1 degrees from 1960 to 2015. The average September temperature fluctuated through the years with the average 2014 temperature being slightly more and the 2015 average temperature being slightly less than 1960’s figure.

- In Okanogan County south of British Columbia, the average March temperature climbed 8.5 degrees from 1960 to 2015. The average June temperature rose 8.1 degrees from 1960 to 2015. Again, the average September temperature fluctuated with 2014 being slightly more and 2015 being slightly less than the 1960 average.

- In Yakima County, the average March temperature increased 7.6 degrees from 1960 to 2015. The average June temperature rose 7.9 degrees in the same period. And again, the average September temperature fluctuated with 2014 being slightly higher and 2015 being slightly lower than the 1960 average.

Those temperatures are expected to continue climbing in the 21st century, according to multiple studies.

“As a scientific community, we’re all pretty convinced it will go up,” said Markus Keller, viticulture professor for Washington State University, whose research station is based in Prosser.

Questions will surface about increasing average temperatures in specific regions — such as the Olympic Peninsula vs. the Yakima River Basin. Will some vineyards need to be established at higher elevations? How will vineyard managers adjust to accommodate the temperature increases and the earlier runoff from the Cascade Mountains? How will soil type influence new plantings? Will the climate changes prompt new grape varieties to be planted? Should new varieties be grafted onto existing varieties?

How many of these potential changes will be driven by economic and market forces? For example, perhaps consumers will prefer the tasting profiles of these new wines produced from new locations.

“We don’t know. We don’t really know,” Keller said.

Experts outline topics for symposium

Wade Wolfe, owner/winemaker of Thurston Wolfe Winery in Prosser with a Ph.D. in plant genetics, said, “It will probably take a generation or two before things are pronounced enough to alter where we’re growing grapes, but also what we’re growing.”

Washington’s viticulture and climate experts are working on an outline for a 2017 symposium to discuss this topic.

These issues have materialized elsewhere, however. For example, Oregon’s Willamette Valley was too cold to grow wine grapes in the 1950s. Today, increased temperatures have turned that valley into a premier place for wineries.

Meanwhile, wine grapes are being grown worldwide at higher elevations. In Europe, they establishing more vines in England and Scandinavian countries. Australia’s vineyards have expanded south into Tasmania. Altitudes that historically have been too cool to ripen wine grapes now can accommodate varieties that are popular. Lower altitudes might be more conducive to other types of grapes.

Greg Jones, a Southern Oregon University research climatologist specializing in viticulture, said, “If you were growing a given variety in its climate sweet spot at 1,000 feet, and the climate there warms by two degrees, then you could go up to 2,000 feet in elevation to find the same two-degree cooler climate that you used to have. This is an all-else-being-equal scenario.”

Eastern Washington is home to nearly 60,000 acres of vines, and Ste. Michelle CEO Ted Baseler predicts the figure can grow to 200,000 acres. There are less than 100 acres established in Western Washington, but some experts can envision scenarios that would allow as much as 2,000 acres of vines.

Overall, Keller estimated that Washington’s wine grape acreages could grow 7 to 9 percent annually for the next 20 years.

Keller speculated all this will likely lead to an increase in Eastern Washington’s red wine grapes such as Cabernet Sauvignon, Syrah and some Italian and Spanish varieties. Meanwhile, he theorized that some white wine grapes such as Riesling and Gewürtztraminer, may decrease in proportion. He also sees the Concord juice grapes phasing out.

Longer growing season for Puget Sound

In the Puget Sound, Jones and Keller believe a couple degrees increase in temperatures could lengthen the growing seasons there. As a result, the viability of Riesling, Chardonnay, Pinot Noir, Pinot Gris and Pinot Blanc would increase, while European-American hybrids would decline.

But while increasing temperatures may prompt movement of vineyards sites for particular grape varieties, those same warmer conditions are already playing havoc with the water needed to grow those grapes.

Less snow is accumulating in the Cascade Mountains because of global warming – and that decreases the water flowing in river basins such as the Yakima Valley. And what is melting does so earlier in the year – stretching the dry season for Washington’s wine grapes, particularly late into the year.

“Snow melts will become a big issue,” Keller said. “It is already a big issue.”

That translates to the biggest masses of water flowing through Eastern Washington’s vineyard country early in the year, and not as much in summer and early autumn precise irrigation is required.

This becomes apparent in the Roza Irrigation District, which stretches from Moxee almost to Benton City along the Yakima River. The reservoirs feeding the Roza are full in the spring, but they are largely drained by the end of summer in some years.

In 2015, the Roza district had about 44 percent of what it needed in June and 47 percent in September. It ran out of water Oct. 12, when it needed to stretch that supply out to Oct. 30. This year was better with the district getting 86 percent of what it needs by June.

Roza manager Scott Revell said his system is not set up to handle irrigation conditions such as those he faced last year.

“Even with 30-plus years of aggressive water conservation measures and 11,000 acres of comparatively drought-friendly wine grapes planted, Roza really struggles to operate the system below about 50 percent supply,” Revell said. “We severely restrict water deliveries, lease as much water as is possible, activate our pumpbacks, shut the canal down for three-plus weeks in the spring, and the farmers who have emergency wells start using them.”

Wine grapes make up 15% of Roza crops

Of the Roza district’s 72,473 acres of crops in 2015, 11,007 acres were in wine grapes. Another way to look at it is that 15 percent of Roza’s crops are wine grapes, which is the largest of the 19 agricultural uses for the district’s water in 2015.

Irrigation for those with junior water rights is spread evenly among all 72,000 Roza customers after the senior water rights holders in other districts obtain their Yakima River water. Roza holds senior water rights only for the final two weeks in March. Consequently, Revell’s district was forced to acquire $1.4 million worth of water from senior districts last year.

All this translates to a need for more ways to store and shuttle water around between the Cascade Mountains’ peaks and the Roza district, including its vineyards.

Right now, the Yakima basin’s reservoirs can save about 50 percent of what is needed, Wolfe said. And the bulk of that water flows into the Yakima basin from March to May, when most irrigators don’t require as much.

“We need to increase reservoir storage,” Wolfe said.

Irrigators, governments develop strategies

A master plan has been mapped out and begun to work its way through the state and federal governments. Overall, this plan is estimated to cost about $900 million with a tentative completion target of 2034. The price tag likely be split between the state and federal goverments. It is being designed to achieve a delicate balance involving agricultural, drinking water and fish interests.

In broad strokes, the plan includes building a pipeline from Lake Keechelus — main source of the Yakima River and the large lake that Interstate 90 travelers pass a few miles east of Snoqualmie Pass — to nearby Lake Kachess. The arrangement is intended to increase the storage for Lake Kachess and allow for more available water to the Yakima basin later in the year when needed.

Dams will be upgraded or established in connection with other Yakima tributaries to help reservoirs collect more water to release at times better for grapes, other crops and fish. These spots include Lake Cle Elum and Bumping Lake east of Mount Rainier National Park in addition to near where Lmuma Creek meets the Yakima River south of Ellensburg.

Plans call for equipment to installed along the Naches River near Yakima to pump out water during early-year high flows and store it underground for lower-flow periods late in the year.

The master plan also calls to federal and state agencies to pursue ways to allow more fields to go fallow as a way to prioritize and save water. Improved methods to transfer water between irrigation districts also will be explored. Irrigators also expect more studies to determine if transferring water from the Columbia River to the Yakima basin is feasible.

A backdrop to the diminishing Cascade Mountains snow melts and the subsequent decrease in season-long irrigation water is Gov. Jay Inslee’s campaign talking points about climate change and global warming. He is seeking to place caps on industrial carbon emissions.

Leave a Reply