WALLA WALLA, Wash. — Grapes are swelling in the hot Walla Walla Valley summer, with the leafy canopies doing their best to shield the ripening fruit from the fiercest of the sun’s rays. It looks primordial, timeless. And indeed, grapes have been grown and crushed into wine for at least the past 6,000 years.

But for 99.9% of that time, no drones have been involved.

Although some things about the relationship between soil, water, sunlight and grape vines would still look familiar to a grape grower in 4000 B.C., the times they are a changin’ in Walla Walla Community College’s Stan Clarke Vineyard and College Cellars.

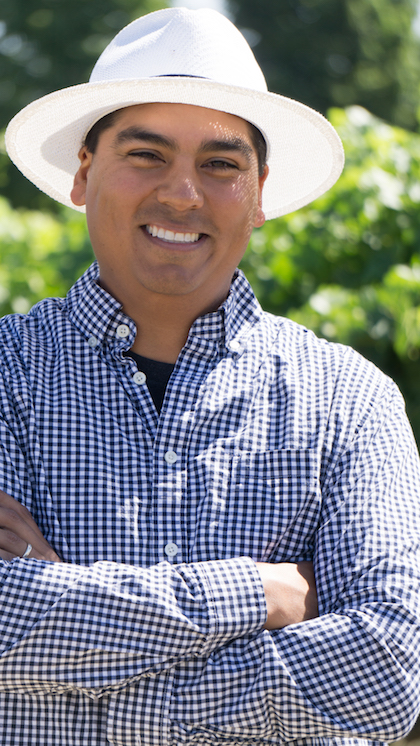

Last summer, the college’s enology and viticulture program hired a new director of viticulture/vineyard manager. Joel Perez replaced Jeff Popick, who retired soon after the class of 2016 graduated.

“We are definitely trying to make the WWCC viticulture program a center of excellence,” Perez said. “I want to push the limits of what we can do in Washington viticulture and promote forward thinking.”

Perez transitions from Marines to viticulture

He came to Washington in August 2011 after his final Marine Corps duty station in Twentynine Palms, Calif. He brought with him 10 years of Marine Corps service and a bachelor’s degree in literature from San Diego State. His wife Vanessa is also a Marine.

At Washington State University Tri-Cities in Richland, Perez earned a bachelor’s degree in viticulture and enology and a master’s degree in horticulture with an emphasis on grapevine physiology. He worked with renowned researcher Markus Keller, the Chateau Ste. Michelle Distinguished Professor in Viticulture at WSU.

Under Keller’s tutelage, Perez tackled several problems unique to the Pacific Northwest wine industry, including virus identification, irrigation and water management, rootstock trials and late-season grape dehydration.

“After you study with Markus Keller you know more about grape vine physiology than you ever thought was possible,” Perez said.

He’s also quick to praise WWCC’s enology and viticulture program.

“Tim Donahue, the director of winemaking, is a tremendous winemaker,” Perez said. “You can give him good grapes, and he can make you a tremendous wine. And in fact, you can give him bad grapes and he can still make some pretty good wine. I can’t say the same thing for a lot of winemakers.

“College Cellars has received well over 700 awards for its wines, but when Tim arrived here, we had about five,” Perez added. “He’s just that good.”

John Deere donates Field Connect to College Cellars

Perez goes on to explain why his vision on arrival at WWCC included bringing a drone and other high-tech tools into the vineyard.

“My goal is to make us as successful and as well-known in the realm of viticulture as we are in enology,” he said.

The first change he made in the vineyard was the installation of a water monitoring system. After speaking to his colleagues at WWCC’s John Deere program, he found his way to RDO Equipment, the John Deere dealer in Pasco. There he met two graduates of the WWCC John Deere Technology Program, Dick Muhlbeier and Chip Lembcke.

Perez remembers that he contacted RDO hoping to convince them to donate Field Connect, a field and water monitoring system, to the college.

“I walked in there to make an argument about why they should help our program with a water monitoring system,” he said, “and I was prepared to shake hands and kiss babies, but because they were WWCC grads, by the time we were five minutes into the conversation they were committed to helping us out.”

About a week later, Lembcke showed up at the college’s vineyard to install a weather station, a five-foot moisture probe, a wetness sensor and a solar panel. Using this system and his phone, Perez can tell at any time how much water is in the soil profile down to five feet deep. He can access wind speed and direction, relative humidity, calculated solar radiation and growing degree days.

In exchange for this donation, John Deere is using Stan Clarke Vineyard as a demonstration site.

While grapes certainly grow without these gadgets, Perez said, “All of these things are modern ways for any agriculture professional to make informed decisions.”

McKibben sparks Verizon donation of drip-line sensors

Once the water monitoring system was installed, Perez heard from another RDO staff member, agronomist Erin Hightower. John Deere was investing in a new drone and wanted a demonstration site. Walla Walla Community College was happy to accept the offer, although it does not employ a drone pilot. Using a drone in the vineyard required approval from the Port of Walla Walla, on whose land both the vineyard and the Walla Walla airport are located.

The first drone flight revealed a divot running down the center of the vineyard’s Bordeaux block, a subtle elevation difference that had gone unnoticed. At the same time, coincidentally, viticulture students were doing insect scouting and discovered a small outbreak of blister mites. As it turned out, the infestation occurred exactly along the line of the divot revealed by the drone. This effect is still unexplained.

Recently, Verizon contacted WWCC about another donation and another demonstration site, thanks to a referral from Norm McKibben, one of the Northwest’s most respected viticulturists. The Verizon system uses sensors in the drip line to monitor how much water is being delivered, and Perez will input into its model the plant moisture information he obtains from leaf pressure bomb tests, as well as vine spacing, and the system will model grapevine dehydration. The system then uses that information to report how much water the next watering session needs to deliver, and when that should take place.

Verizon also plans to install another type of soil moisture probe that works off of electrical conductivity. These were donated by Decagon Devices, a Pullman-based company that produces a variety of agricultural monitoring devices.

Marveling at the number of donations, Perez said, “There’s a huge community in Walla Walla, and in Washington, that wants to see us succeed. It’s just a matter of opening the door and letting people help us.”

Vineyard practices continue to evolve at College Cellars

Perez is also making changes in vineyard practices.

“We have moved full-force on organics,” he said. “I am not a 100 percent believer in organics, but I am a 100 percent believer in education. So, in our curriculum now we’re talking about what ‘organics’ really are.

“Are we talking about USDA Certified organic or organic practices or biodynamics? What does the term sustainability even mean?” he continued. “Everything that we sprayed this year has been organically certified because I want to demystify the term organics and to quantify the effect of their use. If I spray for cutworms at three pounds to the acre of bacillus thuringiensis at $89 for a five-pound bag, is that economically viable compared to spraying two pounds to the acre of a conventional fungicide?”

However, he is becoming increasingly convinced about the value of the organics he used. Because the area had a very wet and cold early part of the season, many vineyard managers faced powdery mildew. So far, the college’s vineyards haven’t seen any.

Perez has also been coordinating with the college’s Water Center on native plant introduction. He hopes to have native sagebrush and rabbitbrush planted around the vineyards because they house beneficial insects but don’t require any extra effort to maintain.

He also is shifting to using primarily foliar sprays, to bring up yeast available nitrogen levels, in order to produce higher quality grapes while minimizing soil chemistry intervention and reducing the amount of nutrient additions needed in the cellar.

Focusing on what Perez calls “clean, low-impact viticulture practices” he is working with Low Input Viticulture and Enology (L.I.V.E.), which is an Oregon-based certification program for vineyard sustainability and with the Walla Walla Valley’s VINEA, the Winegrowers Sustainable Trust.

UberVines will lead students toward sparkling wines

In an effort to promote the planting of more cold-hardy grapes, he has planted seven Chardonnay clones in a trial and will be establishing six clones of conventionally grown Pinot Noir and two clones of Pinot Meunier as UberVines. The grafted UberVines come in to the customer larger than regular rootstock, with an extra-long rootstock cane. The UberVines cost more initially, but also allow you to harvest a year earlier. Perez and the incoming EV students will be discussing the economics of those choices.

The absolute upside: Donahue and the enology students will use the new Chardonnay, Pinot Noir and Pinot Meunier to make a traditional Champagne-style sparkling wine for College Cellars as soon as the new vines are producing.

“I don’t think enough people know about the great things we’re doing here in the Walla Walla Valley,” Perez said. “I think we have a real opportunity to showcase Walla Walla to the world. So I will continue to shoot for the stars, and if I only hit the stratosphere, I’ll take it!”

And where does all this leave the many small, underfunded vineyards who do not have the luxury of virtually unlimited funds and/or donations?