RICHLAND, Wash. — Barnard Griffin Winery’s Rosé of Sangiovese has blossomed into a harbinger of spring each year for wine lovers touring the Yakima Valley around Valentine’s Day.

And for the past decade, Barnard Griffin arguably has been the best rosé producer in the United States. Judges at the 2018 San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition, the largest judging of wine in America, voted the Barnard Griffin rosé as the best of week-long judging. It marked the sixth rosé sweepstakes win at the Sonoma competition since 2008 for the Richland, Wash., winery, so when that wine was unveiled to the panel on Jan. 12, it came as no surprise to Ellen Landis, viewed as one of the country’s top wine judges.

“It was gloriously expressive, and it took me to Washington and Barnard Griffin,” said Landis, a longtime sommelier and journalist who worked in the Bay Area wine trade before moving to Vancouver, Wash. “It’s a classic Sangiovese rosé – floral notes, red cherry, dried strawberry and subtle sweet herbs, with vibrant acidity. The beautiful characteristics carry seamlessly from the engaging aromatics through the lively palate to the lingering finish. It’s a perfect New World dry rosé.”

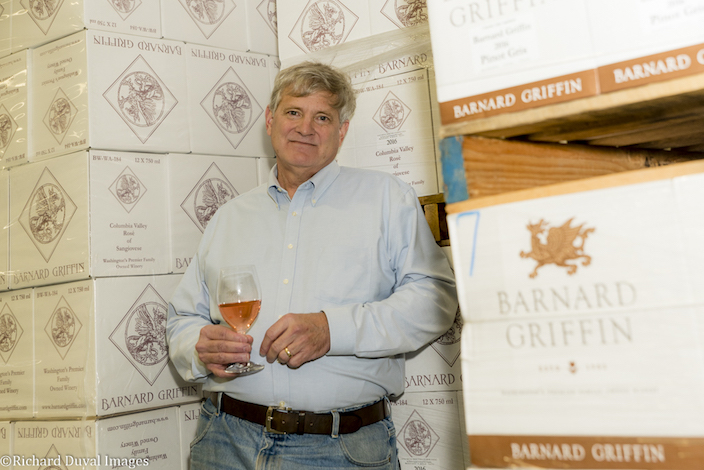

Rob Griffin, the dean of Washington winemakers, releases his 2017 pink to the public on Valentine’s Day, and it will be sold at his Richland winery for $14. Bottling of that wine will approach 17,000 cases. That electric pink, which is devoted to the Italian red grape variety, accounts for about 25 percent of the total production at the two-generation wine company. And it’s the largest of its kind in the Pacific Northwest.

“That’s more than I thought I would make. There’s not a lot of that variety up here, and there are other people using Sangiovese for rosé — including Charles Smith, who tends to be more charming than me,” Griffin said with a chuckle.

Barnard Griffin rosé earns respect in California

Mike Dunne, wine columnist for the Sacramento (Calif.) Bee, reviews the top wines at the Chronicle. He continues to be impressed by Griffin’s skill at transforming the grape most commonly associated with Chianti-style table wines into Northwest’s best-selling homegrown rosé vintage after vintage.

“I’ve always liked it,” Dunne said. “I like how forward it is. Vibrant. I think that’s Sangiovese. I’m surprised more wineries don’t exploit Sangiovese in that way. Two of those three rosés in the sweepstakes (at the San Francisco Chronicle judging) were Sangiovese.”

The competition’s archives reveal that Barnard Griffin also captured the top honor in 2016, 2014, 2012, 2011 and 2008 — the first year that the Chronicle tasked its judges with determining a sweepstakes award for rosé. Starting in 2006, the BG rosé has won a gold medal in 12 of the 13 years it’s been entered. The first year entries beyond California were allowed was 2005.

“The one year it didn’t win a gold there that same wine (the 2012 vintage) won two other sweepstakes, so go figure!” Griffin said with a chuckle.

Those years of acclaim and headlines in the U.S. wine industry’s most important newspaper, marketing influence and consumer acceptance fueled Barnard Griffin’s rise among U.S. rosé producers, particularly with Sangiovese.

“I can’t tell you for certain, but according to Nielsen, we were the first ones to promote that category,” Griffin said. “It gets me on the radar of people who have atomic bombs in the marketing world, and we come up first on the Nielsen scan.”

It’s become so personally important to Griffin — a proud graduate of the storied University of California-Davis winemaking school — that he focuses a significant chunk of his professional attention each year on the development of his rosé. He remains the company’s director of winemaking. His daughter, Megan Hughes, heads up the white wine program. Mickey French, Griffin’s longtime right-hand man, quarterbacks the red wine production.

“That leaves me with the rosé, and I love it,” Griffin said. “We share the responsibility on everything, but I take the rosé very seriously.”

Balcom & Moe remains ‘backbone’ of Barnard Griffin rosé

Griffin referred to one of his longtime friends and most trusted growers, Maury Balcom and his vineyard north of Pasco, Wash., as “the backbone” of his rosé program. Their sudden success, starting with Barnard Griffin’s 2002 Rosé of Sangiovese, prompted Griffin to not only look for other growers of that variety but also to get Balcom & Moe Vineyard to plant an additional 7 acres of Sangiovese a year ago.

“In the beginning, that first year at least, it was 100 percent of the program,” Griffin said. “The way that Sangiovese yields and the way we farm it, (the variety) produces a lot of fruit.”

At one point, Watkins Vineyard near Pasco sold all 4 acres of its Sangiovese to Barnard Griffin for rosé. In recent years, his Sangiovese pipeline has grown to include fruit from the Gunkels near Goldendale, Colin Morrell of Lonesome Spring Ranch in the Yakima Valley, the Tagarres family’s Michael Vineyard and several other sites throughout the Columbia Valley.

“It’s been kind of a steady growth,” Griffin said. “In 2016, we went from 15,000 to 20,000 cases. That’s because the fruit was there. In 2017, we were not able to get as much.”

The 20,000 cases bottled from the 2016 vintage stands as the record, and Barnard Griffin’s prescience to sync up with the worldwide thirst for rosé seems uncanny. By Valentine’s Day each year, the supply chain is poised for the latest bottling.

“We still have a trivial amount (of the 2016), and it will be gone before the end of month,” Griffin said.

His family and staff would prefer to have fans buy it at their tasting room on Tulip Lane, but bottles are widely available throughout the Pacific Northwest.

“An astute customer can find it for a better price,” Griffin said. “It’s been big in QFC, Safeway and Albertsons, and Yoke’s (in Eastern Washington) has been as big of supporter as any chain account. It’s also big in independent stores and PCC around Seattle. Trader Joe’s in Portland seems to do really well with it for some reason.”

Along the way, Griffin continues to struggle with his controller’s natural inclination to ask customers for another dollar or two.

“You mess with the price and you really cause some problems, so I’m making more rather than charging more,” Griffin said. “That might be making a mistake.”

Sangiovese rosé makes sense for grower, consumer

His deft touch with Sangiovese seems to be paying dividends for everyone. Italians historically embraced the variety because the vine is so fruitful and the clusters so large. That defeats the purpose for a critically acclaimed Super Tuscan-style wine, but rosé producers aren’t targeting the traditional benchmark level of ripeness at 24 percent sugar — or Brix — for most red table wines.

Cabernet Sauvignon in Washington state often is cropped at two to three tons per acre to attain 24 Brix. Prized vineyards of Pinot Noir in Oregon’s Willamette Valley sometimes are constricted to eke out less than two tons of wine grapes per acre. Those vines require more labor and management, which explains why those Northwest wines routinely are priced at $40 to $80 per bottle. It easy to see why folks walk out of Barnard Griffin’s tasting room with cases of the rosé.

“In a good year, we can crop Sangiovese to 10 tons an acre, which is almost embarrassing to admit,” Griffin said. “But that gives the wine the crisp acidity, and it still has the fruit. Of course, that’s dependent upon the year. A more average vintage would be seven to eight tons per acre.”

As a result, the science inside the grapes he hopes to harvest for rosé amounts to a sugar level of 21 Brix, a pH level of no more than 3.4, total acidity of 7 grams per liter, a food-friendly alcohol in the range of 12.5 to 13 percent, and residual sugar less than 0.3 percent — essentially bone-dry. In the hands of Griffin, that chemistry makes for gorgeous color with engaging high-toned red fruit aromas and flavors backed by a brisk mouth feel.

“What makes that wine the way it is the acidity,” he said.

Griffin stresses that he grows Sangiovese explicitly for rosé production. He does not resort to the saignée method to “bleed off” juice to make a pink wine. And since Griffin covets fruitiness and acidity rather than sugar, it allows his growers to pick their crop for him earlier. That reduces the stress on the vineyard manager. And it gives the winemaker something for this crush pad team to process during the first half of the harvest while the grapes for their more expensive wines continue to hang and build sugar.

Sangiovese rosé shows versatility at dining table

These days, there are plenty of smiles at Barnard Griffin. This year marks the 35th anniversary of his own company, which he launched after spending eight years at now-defunct Preston Wine Cellars in Pasco. Just beyond the tasting room, workers continue to remodel The Kitchen @ BG and prepare for the restaurant’s reopening in early March.

This weekend, the family returns to San Francisco Bay where it again will pour their rosé for the 5,000 guests of the San Francisco Chronicle Wine Competition’s Public Tasting at Fort Mason. No other Northwest winemaker has worked with Sangiovese for rosé to such an extent, approached Griffin’s level of success and enjoyed it more.

“There’s a fun aspect to it,” Griffin said. “Sangiovese has an inherent sweetness to it, and the tiny bit of tannin gives it some nice structure. It’s surprisingly versatile and works beautifully with salmon and across so many dishes, especially pasta dishes. There’s not much it doesn’t work with in some form or another, including salads, which is not always an easy thing to accomplish.”

Griffin admits that he’s toned down the pink appearance because of the increased interest in Provence-inspired rosé, which tend to be more salmon in color. Never mind. Those subtle adjustments in recent years continue to yield gold medals.

Dunne, the Sacramento critic, follows the Northwest wine industry and serves as an occasional judge for competitions that involve Great Northwest Wine.

“They need to plant more Sangiovese up there, and that’s what I said in my tasting notes for that wine,” Dunne said.

Leave a Reply