For a teen in the late 1960s, in Martinez, Calif., there was much to do, much to see. A war was happening, college campuses were on fire … hippies abounded. But for one young man, only fermentations were on his mind.

“One of my very early forays into winemaking as a high-school student was making wine out of tomatoes,” says Rob Griffin, Washington’s longest-tenured winemaker (46 vintages, au currant). “The resources available to me in Contra Costa County, California, in the 1960s were books in the library on home-winemaking, written by quaint British ladies who made things called hedgerow wines, using sloes. I had no idea what a sloe was. But I happened to have a lot of tomatoes.”

The idea of winemaking isn’t likely on the minds of most high school juniors, especially those without a winery that already bears their surname.

“Ironically enough, it wasn’t for the alcohol — which is a natural assumption, but in my case it was just a native fascination with the process and the ability to alchemically change one thing into another,” he recalls. “I played around with brewing beer, the very first thing I made was mead — honey was reasonably available in my family kitchen — I think I made a grand total of half a gallon. It took forever to ferment, but it was interesting for me to observe the process.”

Napa Valley was ramping up — around 40 wineries called it home — but the region was still several years away from the grand reckoning at the Judgment of Paris, that blind tasting in 1976 that hoisted American winemaking onto the big stage.

“I had an uncle with a vineyard in the Napa Valley, which gave me some exposure to the winemaking process,” he says. “I remember a particularly exciting tour of Beaulieu Vineyards. My uncle was great friends with André Tchelistcheff, who gave us a tour of the facility.

“Beaulieu Vineyard at that time was an old, Prohibition-era California winery that was a little rough around the edges. André was wearing a sparkling white Panama suit with a matching hat, walking around — stuff spraying everywhere, open-top tanks being pumped over, didn’t get a drop on him.”

When it was time to apply to colleges, Rob wanted little else than to go to University of California, Davis, and enroll in the winemaking program.

“Getting into Davis has always been difficult, but I think because I made it very clear that winemaking was my intention; I actually got in,” he says proudly. “In my class there were two Wentes, a couple Mondavis and many other people who had reason to assume they’d have employment upon graduating.”

Post-Davis, Rob took a job thinning shoots in the Buena Vista vineyards of Sonoma, eventually making it into the lab.

“From a practical standpoint, you could have considered me assistant winemaker at that point.”

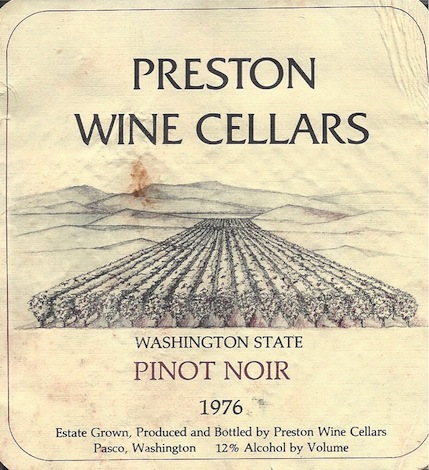

Restless with the position, Rob took a meeting with Bill Preston — a tractor salesman from Washington state who made his way down to California in a station wagon. He was searching for a winemaker for his new winery, then the second biggest in Washington state after Château Ste. Michelle.

“As a junior at Davis, I had taken my spring break and driven up to Washington and nosed around a bit. It was very cold, snow on the ground. Miserable. Why I came here is anybody’s guess … from the verdant beauty of California,” Rob says, a hint of a smile. “I think in retrospect, it wasn’t a bad move, but it was a case of taking the main chance and letting the dice fly high, to quote Caesar.”

The dice landed in Pasco, where Rob was tasked to babysit (ie: fix, finish, blend) an inherited vintage and start down his own winemaking path.

“I worked a ton, and there was a ton of work to do,” he says. “It was basically a farm operation, and on a farm you work until you drop dead.”

Griffin tops Oregon judging with ’77 Washington Pinot Noir

At 24 years old, he finished a Pinot Noir that won an Oregon competition and resulted in Washington wines being banned from entering. His ’77 Chardonnay won the Grand Prize at the Seattle Enological Society’s annual wine competition.

“The feedback and recognition was significant,” he says.

But it was just the beginning.

His winemaking was lauded in the L.A. Times and the San Francisco Chronicle, while Preston became a common mention in any glowing wine reviews of the Pacific Northwest’s newest releases. A calling to make his own wine, for himself and without the shadow of someone else’s brand, ultimately necessitated a move in 1983 to the general manager/head winemaker position for Hogue Cellars in Prosser. The same year, he and wife Deborah Barnard began their eponymous winery, Barnard Griffin.

Barnard Griffin grew on the side, until its size and scope demanded full attention in the early ‘90s. The brand was in need of a home and a winemaking facility, and since Rob and Deborah’s own family had doubled in size, dreams of bursting back into the California wine scene were no longer terribly relevant. Washington was it.

They purchased their Tulip Lane property in 1996, where the winery sits to this day, having expanded both its production in 2008 and its hospitality sectors in 2012.

Throughout a career spanning five decades, Rob’s winemaking has continued making headlines, most recently with rosé of Sangiovese — an electric pink juggernaut that delights all who give it a try. Rob’s mission to produce good wine people could access rings true even in this horrifically inflated present we’re wading through.

“Barnard Griffin has always been wine that people could afford, that’s as good quality as we can make it,” Rob says. “The wine is the show. The product has always over-delivered.”

The winery is entering its 40th year of production, still family-owned, but with two extra names on the masthead; daughters Elise Jackson and Megan Hughes.

With such an early start to a lifelong career, picking a wine that set him on this path is akin to arguing whether it is the chicken or the egg? Come hell or high water, Rob Griffin was going to be a winemaker.

“If there was one … it was when I was a junior or senior in high school. My older brother gave me a bottle of Louis Jadot Moulin-à-Vent. It was so exciting and adult to have my very own bottle. It was a genuine, quality wine that showed me the potential and nuance and art side of it all. That was a revelatory thing for me.”

Few get to spend their lives in the job they dreamed of as a child. Doing even remedial math, one could safely assume Rob is of retirement age. But why retire from this?

“I don’t know how to do anything else,” he jokes. “It’s a family-business, it’s a business in general. I enjoy winemaking — a lot. The whole process is infinitely fascinating to me. I’m out here dragging hoses around and killing myself during harvest, complaining about it, but I still like it. That’s the dynamic, fun part of the business.”

And, when you’ve built a life around your passion, the fun never has to end.

Leave a Reply