MILTON-FREEWATER, Ore. — The federal government has opened commenting on the proposed The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater American Viticultural Area in Oregon’s portion of the Walla Walla Valley, but geologist Kevin Pogue said his petition for the wine growing region is easy to defend.

“I designed it to be what I think is the single-most terroir-driven AVA in the United States,” Pogue told a group of wine writers last summer. “Ninety-seven percent of the ground within the AVA boundary is one soil type — the Freewater very cobbly loam — and it’s on one landform, the Milton-Freewater alluvial fan. It also has a very small range of elevation so in terms of its terroir, it is one unit … which I’m pretty excited about.”

[youtube id=”WBHubDVJbOQ” width=”620″ height=”360″]The U.S. Department of Treasury’s Alcohol and Tobacco Tax and Trade Bureau (TTB) has proposed the establishment, and comments supporting and debating Pogue’s petition run Feb. 26 to April 28. And the Whitman College professor said this area of Umatilla County has been known for its special qualities for nearly a century. Vineyards dating back to the Great Depression can be seen while driving along country roads in the area north of Seven Hills Vineyard.

“They’ve grown orchards and vineyards here since the late 1800s, and I have records that I found for my AVA petition that people were screaming how wonderful these rocks were for growing vineyards and orchards since 1916,” said Pogue, who also operates VinTerra Consulting.

Only wines made in Oregon could use ‘The Rocks’ AVA

One potential issue with wineries using The Rocks designation is that even though it is all within the Walla Walla Valley AVA, it is entirely in the state of Oregon.

By federal law, because it does not cross the state border, only wineries in Washington with a Oregon production facility will be able to use The Rocks on their labels — even if they are in the Walla Walla Valley. Of the three public comments published on the TTB website by Feb. 28, two of them touched on this restriction.

Pogue said he proposed the AVA based strictly on soil type and without regard to state boundaries.

“These are river rocks that are 100 percent basalt lava and were washed down out of the blue mountains by the Walla Walla River,” he said. “This occupies about 3,000 acres, and it fades off the north towards Walla Walla, so we drew the boundaries of the viticultural area to surround the area that has these rocky soils.”

The scale of those cobblestones fascinates wine tourists, Pogue said.

“I will get people on tours who visit and before I get a chance to say thing, they will say, ‘My god, it must have cost a fortune to get all this rock hauled in here!’ ” he said.

Cobblestones fascinate winemakers, tourists

The bi-state Walla Walla Valley AVA was established in 1984, but the concept for The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater AVA didn’t begin until about 15 years later, when Burgundy-born winemaker Christophe Baron arrived in Walla Walla to start Cayuse Vineyards, Pogue said.

“He was driving through here and noticed that it looked a lot like the cobblestones of Châteauneuf-du-Pape in France, and said, ‘Wow, it’s just like Châteauneuf!’ ” Pogue said. “I’ve been to Châteauneuf and have done some terroir stuff there, and it’s not just like Châteauneuf. It’s better than Châteauneuf!

“I’m not saying that just because I love my backyard,” Pogue continued. “I’m saying that because I was in Beaucastel after a heavy summer rainstorm and water was standing in the vineyards and the rocks were poking out. I thought, ‘Wow, that’s weird. How can that be with these rocks? It’s got to be incredibly well-drained.”

However, Pogue said he soon learned the layer of rock in Châteauneuf-du-Pape is just a few feet feet deep and sits upon clay.

“As anybody who has a vineyard here knows, it could rain like Noah’s Flood and there would be no water standing,” Pogue said. “The cobblestones here are on the order of 200 to 300 feet thick.”

At that point, Pogue again made his assertion for uniqueness of The Rocks.

“If they had these soils in Châteauneuf-du-Pape, they’d have trouble even growing grapes because they can’t irrigate,” he said. “They need that clay to absorb and hold the water there. Since we can irrigate, it’s great to have hyper-well-drained gravel.”

19 wineries with vineyards cited in AVA petition

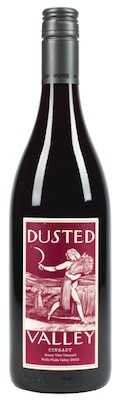

Corey Braunel, co-owner of Dusted Valley Vintners in Walla Walla, said his family purchased land from the Waliser family in 2007 and established their Stoney Vine Vineyard in the proposed AVA because of the unique aspects.

“It’s been exciting,” Braunel said. “The first wines came off the vineyard in 2010, and it’s been a very unique experience. The expressiveness in the wines … it’s like a light switch on and off.”

“It’s been exciting,” Braunel said. “The first wines came off the vineyard in 2010, and it’s been a very unique experience. The expressiveness in the wines … it’s like a light switch on and off.”

Stoney Vine is planted mostly to Syrah — clone 7 and clone 99 in seven by four spacing — and other red Rhône varieties such as Cinsault, Grenache, Mourvèdre, Petite Sirah but also Port-style grapes Tempranillo and Touriga Naçional.

“We’re only hanging about eight clusters per vine,” Braunel said. “The idea is to really get the crop load down and really stress the plant.”

If established, The Rocks District of Milton-Freewater would be the second-smallest AVA in Oregon, with only Ribbon Ridge in the north Willamette Valley being smaller at 3,350 acres. Washington state’s smallest AVA is Red Mountain at 4,040 acres.

Officially, Pogue’s proposed AVA would span 3,770 acres, and the area already has about 250 acres of producing vineyards.

The petition names 19 wine producers that have vineyards within the proposed AVA, and it notes that three of the 19 producers also have winery facilities within the proposed AVA. Those wineries include Beresan, Buty, Cayuse, Charles Smith, Delmas, Don Carlo, Dusted Valley, Figgins Family, Proper, Otis Kenyon, Rasa, Reynvaan Family, Riverhaven, Rôtie, Saviah, Sleight of Hand, Watermill, Waters and Zerba.

Sean Boyd of Rôtie Cellars considered selling his land in The Rocks until he had an epiphany, Pogue said.

“He was attending a tasting group in my backyard,” Pogue said. “We had 22 Syrahs from all over the world we were tasting blind. There were four in there from vineyards within The Rocks, and maybe five of the 12 of us were able to instantly pick out the four Syrahs blind from this terroir. Sean himself was able to do it. I think he kind of believed it true. After that, he was, ‘OK, I’m planting.’ That’s really cool.”

Geologist says heat from rocks can warm grapes 2-3 degrees

Pogue said he’s performed some “crazy research” regarding temperatures of the rocks and grape clusters.

“I wanted to check up on the phenomenon that rocky soils are great for growing grapes because they heat up during the day and they keep the vineyard warmer at night,” Pogue said. “That’s crap! That’s absolute fundamental bullshit! And I’ve got the numbers to show that.

“I’ve shot these rocks with a thermal imaging monitor and got temperatures of 135-140 degrees in July,” he continued. “So yeah, they heat up very quickly, but physics says anything that heats up quickly also cools down quickly. It’s heat transfer. It works both ways.

“In the day, they are radiating heat and energy, but right after sunset, that goes away very quickly. These vineyards are no warmer at night than any other vineyards in the valley. In fact, because they are lower elevation and the rocks aren’t radiating heat, in some cases, they are cooler than other other places in the valley.”

Pogue said his research indicates clusters trellised closer to the rocks can be 2-3 degrees Centigrade warmer than if hanging over a cover crop of grass.

“This is one of the only places in the Northwest where you don’t have to have a cover crop,” he said. “You don’t have to worry about the soil eroding or blowing away.”

The Rocks District can suffer from frost damage

The heat transfer from the rocks also works in the direction of the roots, Pogue said.

“Once the heat gets down where there’s water in the soil profile, the water absorbs that heat and holds onto it,” he said. “So it heats up the soils, and it radiates heat to the vines, but it doesn’t warm the air in the vineyard at nighttime.”

That also explains why vineyards in the Milton-Freewater area have suffered from freeze damage in recent years.

“It does have an Achilles heel,” Pogue said while pointing to nearby wind machines. “It is kind of cold here sometimes in the spring and the fall, colder than the vineyards in the hills.”

It took more than 13 months from his petition to progress from the “accepted as perfected” status to the public commenting period. Karen Thornton of the TTB’s Regulations and Rulings Division is overseeing the petition that Pogue is so passionate about.

“These gravels end right at the base of the hills,” Pogue said, pointing to Heather Hill and Seven Hills vineyards. “It’s like a knife. You cross that line, and you are in a completely different soil. Chemically, texturally, thermally – everything.”

Very nice article. I’m thinking the 3 wineries located in OR are Watermill, Zerba, and maybe Riverhaven?? I’m assuming other Oregon wineries that source fruit there could also use the AVA on the label, though the article doesn’t mention that possibility. Domaine Serene and Fauss Piste are two I’m aware of that have Syrahs from the area.

Good for all of them, but if the WA wineries that have made the area famous (i.e. none of the 5 I listed) cannot use the AVA label it is pretty academic, imo, and serves no real purpose in the marketplace, which is really a big part of AVA designation and labeling in the first place, no?

I can’t help but compare to the Washington’s Rattlesnake Hills AVA where a big chunk of the wineries, even many of the “big” names with vineyards located there (Sheridan, Cote Bonneville, Andrew Will, etc…), decline to use that label designation for marketing reasons.

I appreciate Dr. Pogue’s efforts and being true to the geology, but if most cannot use the label on a bottle of wine, what’s the point?

Chris,

All good points. I suspect something will get worked out. Perhaps someone sets up a facility on the Oregon side of the border, then other wineries that want to use the designation could be bonded there. That could well satisfy the requirements.

The 3 wineries in Oregon are Watermill, Zerba & Don Carlo.

To add to my comment, I read the current other comment to the TTB. The suggestions to include WA wineries are good ones, but I’d suspect the petitions would have more weight with the TTB if WA winery owners, and even the petitioner Dr. Pogue would make this appeal. Maybe they have through other channels. It will be interesting to see if and when the AVA gets approved, how it gets tweaked, and used by the industry.

Last time I looked, Cayuse was in Oregon also.

Great article! I often wondered why they didn’t go for their own AVA. It IS confusing for my staff and guests who don’t understand that the Walla Walla Valley is in both Oregon and Washington.

Great article “The Rocks” will provide a unique part of the Walla Walla valley to Market the fine wine that this area grows. I grew up in Milton-Freewater and know all about the soils that produced green peas,onions,Italian Prunes as well as Italian wines from the vines off of The Rocks. Milton-Freewater is sitting on industrial property that could allow for multiple let alone large wineries to custom press and clean with the Wastewater system built for the Pea Canneries that once drove the towns economy. Take advantage of what is sitting idle and promote the AVA as well as the Walla Walla valley’s beauty and vines. Keep up the great writing as I enjoy reading even if I find your old printed ones Online. Thanks

One of key aspects of branding an AVA is to have a name that consumers can remember, and look for wines from that AVA. The proposed name is impossibly long for the average consumer to remember, and it also sounds like it belongs to a particular person or business, with “Milton Freewater” in the title. I suggest agreeing on a much shorter name for the AVA, which may actually help sell more wine. Maybe “The Rocks” is enough. It definitely has the “cool factor” for consumers to easily recall. I’m not sure of possible issues with that name already being protected in Sonoma County.