Editor’s note: This is the second of a two-part report on the influence of climate change and how it might affect the Washington wine industry.

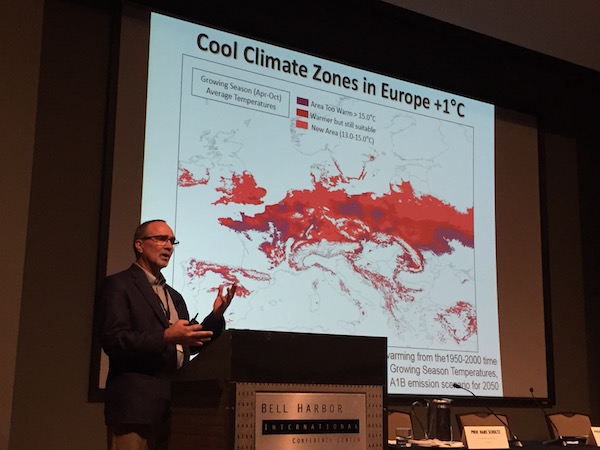

There are an estimated 80 acres of vineyards in the Puget Sound region, but researchers believe changes in the climate could make for exponentially more possibilities.

Greg Jones, a climate researcher at Southern Oregon University in Ashland, said he believes climate change might create the potential for that to grow to as much as 2,000 acres in the next 20 years. Vines could scattered throughout the Skagit River basin, the Olympic Peninsula and islands throughout the Puget Sound.

He conducted the most recent major survey of vineyard potential throughout the Puget Sound in 2007,when he examined the northern and eastern sides of the Olympic Peninsula. His study came up with an almost-2,000-acre estimate for the peninsula’s potential. Other experts agree.

“Overall, the North Olympic Peninsula region provides sound potential for cool-climate viticulture and presents an interesting development for the industry in Washington and beyond,” Jones stated in a climate report. “The region will benefit from its proximity to a large market and should capitalize on the ability to grow unique grapes with a light, crisp, and aromatic style of wine that pairs well with the seafood of the region.”

There are no major sweeping areas on the peninsula that are ripe for vineyards, Jones said. Instead, the peninsula is sprinkled with pockets featuring proper soils at viable elevations heated by suitable temperatures and other conducive climate conditions.

His report recommended that new vineyards follow grape varieties already established throughout the Puget Sound or being tested at the WSU Northwest Washington Research & Extension Center in Mount Vernon.

For white wines, that would be Madeleine Angevine, Sylvaner, Siegerrebe, Chardonnay, Pinot Gris, Riesling, Müller-Thurgau, Pinot Blanc and Gewürztraminer. For red wines, suggested varieties include Pinot Noir, Zweigelt, Garanoir, Maréchal Foch, Leon Millot, Agria and Regent.

Washington wine industry can look south for signs

California is already grappling with its climate change issues – a preview of what Washington might face.

Several years ago, Californian officials and scientists began identifying climate change as a major concern for that state’s wine industry. The questions came down to how much will change and how fast?

A Stanford University report published in 2009 stated, “Current trends indicate that temperature and water levels are changing in a way that jeopardizes many of California’s climate-sensitive industries, in particular the wine industry.”

The study looked at California’s premium grape-growing regions of Napa, Sonoma, Mendocino and Lake counties.

Climate scientists at Scripps Institute of Oceanography at University of California-San Diego predicted that California will see an average increase in temperatures of 0.9 to 3.8 degrees Fahrenheit during the next 25 years, according to the Stanford report which is now seven years old.

“However, it is unclear whether future climate change will strengthen, weaken or disrupt these ideal conditions currently present in premium California wine growing regions. … However, the wine industry is beginning to signal that the state can and must play a greater role in helping the industry prepare for and adapt to the long-term impact of future climate change,” the report said.

California’s shrinking water supply is the biggest short-range problem, but the rise in temperature will be the most important long-range issue, according to Stanford researchers.

“There is significant demand for the state to play a greater role in helping the industry adapt to potential climate change,” the report concluded.

In 2007, there were an estimated 2,300 wineries in California, and they are fed by 4,600 vineyard sites spanning 625,0000 acres. The Stanford report said the overall economic effect reached $52 billion. California produces about 90 percent of the nation’s wine, and wine accounts for about 3 percent of its gross state product.

There are parallels between how climate change is expected to affect both California and Washington.

A 2011 study by Noah Diffenbaugh, Stanford University earth systems sciences professor, indicated a conservative estimate is that average temperatures in California will increase by two degrees by 2040. Under that scenario, he estimates that would negatively impact 50 percent of those vineyards designed for premium wines production. That vineyards account for about 25 percent of the industry.

However, John Aguirre, president of the California Association of Winegrape Growers, is skeptical that climate change will affect his state’s vineyards.

While vineyard owners are pondering the heat of the past two years, Aguirre said market conditions – not climate change – is what affects the industry in California.

“I’m not aware of a single traditional grape-growing winery that is shifting because of climate change or changing because of the weather,” Aguirre said. “I’m not sure climate change is part of the conversation.”

Research calls for monitoring consumers, critics

In fact, because of economic reasons, Aguirre sees California as expanding its production of premium wine – the types of higher-priced wine that Diffenbaugh’s work identified as being threatened in the next 25 years.

As for climate change mitigation measures, the 2009 Stanford report recommended:

- Expanding water storage facilities

- Creating tax incentives to encourage winemakers to shift to grape varieties better suited to new climate conditions or plant new vineyards in cooler areas

- Monitoring trends in sales of certain wine varieties, wine scores and wine prices to determine if consumers, winemakers and judges are becoming more rigid.

“Cultural change is nearly always a slow, gradual process, so the State should not give too much attention to dramatic changes in consumption, scores, or price in any given year and instead look to long-term trends to determine where the industry is headed,” according to Stanford researchers.

Wineries can experiment with new winemaking techniques such as adding oak tannins or oak chips to grapes during winemaking to increase the acidity and decrease the alcohol content of wine, the 2009 report said.

Other climate adaptation measures include:

- improving irrigation systems

- allow vines to develop more canopy in order to provide better shade for grapes to battle additional sun exposure

- embrace spraying of organic pesticides

- grafting new heat-resistant grape varieties onto existing grape rootstocks

- planting disease-resistant clones of existing rootstock

But that same report noted that planting new rootstocks and expanding vineyards are extremely expensive measures that not all growers can afford. Also, ecological ripple effects could occur from changing irrigation. The report also pointed out that in the Napa Valley, changes in irrigation could harm the migration of endangered fish.

A Washington version of that problem could stem from Okanogan County vineyards expanding into bear habitat, said Lee Hannah, a climate change ecologist with Conservation International. The researcher at UC-Santa Barbara also studies global warming’s effects on viticulture.

Anticipated changes in wine flavors, structure

Another factor in dealing with climate change’s effects on grapes is taste. How will wine consumers adapt to inevitable changes in the drink’s structure and flavors? So psychology also is expected to play a significant role in how the wine world will deal with climate change.

“There is a challenge to get consumer acceptance of different types of grapes,” Aguirre said.

The 2009 Stanford report predicts consumer preferences will change, winemaking practices will change and even the opinions of wine judges can help determine which wines are in vogue. “For example, many growers are hesitant to graft different, heat-resistant grape varieties such as Emerald Riesling and Ruby Cabernet onto existing rootstocks for fear that consumers will simply not purchase and drink nontraditional wines,” according to the report. “Thus, the extent to which the impacts of future climate change will be mitigated by winemaker or grower behavior is uncertain.”

The 2009 Stanford report noted a physical and economic ripple effect from judges’ scores at tastings – which would affect the willingness of wineries and vineyards to experiment with changes in their grape growing.

In other words, will the wine world accept these expected new flavors?

The 2009 Stanford report cited Oregon researcher Greg Jones saying that if a wine score rises from 80 points to 90 points, its price will likely double. And if that wine score increases to 95 points, its price can be expected to increase by 350 percent.

Those figures help explain why critics’ preferences often determine trends, which can encourage or discourage wineries and their growers from experimenting.

A Stanford graduate business school study from 2008 observed that people drinking from two bottles of the same wine — one priced at $5 and the other labeled as $45 — will more likely say the wine from the expensive bottle tasted better.

The 2009 Stanford study said: “Two narratives, one rigid and one flexible, account for the most likely and relevant cultural outcomes that will affect the ability of the wine industry to adapt to climate change. In the face of increasing globalization, new wine consumers may be overly influenced by traditional judges and varieties, and therefore attracted to the austere wines of the past. This could lead to a global preference for certain wine (varieties) that narrows … making adaptation through substitution extremely costly and difficult.”

New consumers, new varieties

Predicting the preferences of millennials and the next generation is anyone’s guess.

“Alternatively, increasing globalization could bring new consumers, winemakers and judges that are open-minded and therefore attracted to softer, fruitier wines that will provide more space for growers and winemakers to adapt,” the 2009 Stanford study stated.

On Lopez Island Vineyard, owner/winemaker Brent Charnley said he’s betting on the second scenario.

He remembers when Puget Sound wineries routinely generated mediocre scores at tastings and competitions, theorizing those wines tasted different from the mainstream. Now, Puget Sound wineries are collecting gold medals in those competitions.

Charnley said he believes people have become more comfortable with trying new wines and varieties.

“The newer generation is much more open-minded,” he said.

And he adds that Washington winemakers have been willing to experiment.

“There is a lot of tinkering going on, and I expect it to continue that way,” Charnley said

Leave a Reply