WALLA WALLA, Wash. — The official word from the Washington State Wine Commission is that Washington enjoyed a record grape crop in 2016. Growers and winemakers alike were thrilled with the 270,000-ton harvest, which far surpassed 2014’s record of 227,000 tons.

The entire growing year was unusual, beginning with the earliest-ever start to the growing season. Washington growers saw the earliest bud break, the earliest bloom and the earliest beginning of veraison on record.

Following the early and unexpected spring warmth, the summer was cooler than those of the previous three vintages, which slowed ripening. This allowed the growers to leave fruit hanging on the vines longer than usual, accumulating sugars. However, the relatively cool nights, even in the midst of summer, resulted in the preservation of great acid levels, to balance the sweetness of the fruit.

All in all, 2016 seems poised to go down in the books as one of the most perfect growing seasons anyone recalls.

ETS presents findings to Walla Walla wine industry

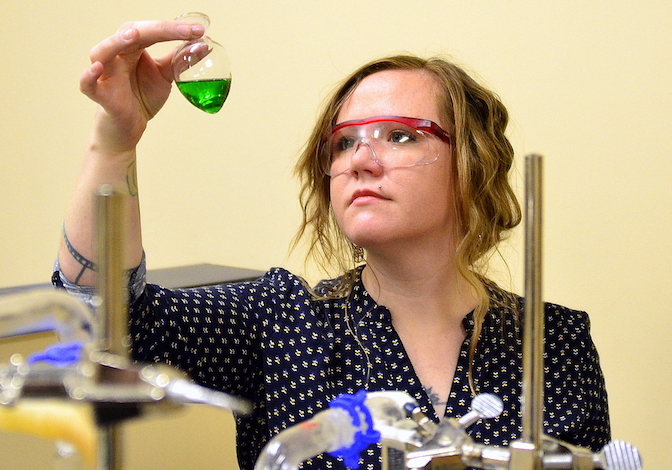

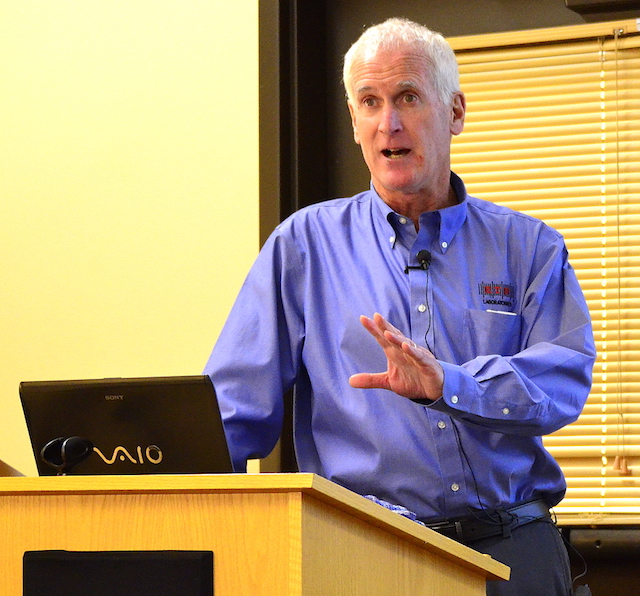

In order to move the discussion of the harvest from the anecdotal to the scientific, ETS Laboratories in St. Helena, Calif., whose sole business is the analysis of wine samples and wine data, and conducting wine-related research, presented a post-harvest seminar at the Walla Walla Community College’s Center for Enology and Viticulture. Attended by local winemakers and students, the Feb. 23 seminar cast light upon the chemistry of the 2016 harvest.

When we drink wine, we often don’t think about the data and analysis that went into producing our daily glass. But from the moment grapes begin to ripen, growers monitor sugar and acid levels, as well as check them for the myriad nutrients that vines need to produce premium wine grapes. The vineyard and the cellar generate data all season long.

Richard DeScenzo, microbiology group leader with ETS, said “primarily my job is helping people to understand their data.”

Wine chemistry governs the pick date of the fruit and directs a cascade of stylistic, aesthetic and sanitary winemaking choices. If a wine pleases you, the chances are good that the grape grower and the winemaker put a lot of time and effort into analyzing the wine as it developed from juice to bottle and making chemical and physical adjustments to the wine to keep it on the path to perfection.

DeScenzo listed a number of factors related to the meteorological conditions Washington experienced during the 2016 growing season. Each helps illustrate why vintage matters.

Across Washington, the pH in grape juice was down significantly, so acids were higher than last year and sugars were down. The result of the grapes having lower fermentable sugars is that alcohol levels in the 2016 vintage will be lower. For those with an Old World palate, 2016 will be a very good year in Washington wine.

All forms of nitrogen were higher, probably because of the rains just before harvest, so growers didn’t need to add as much nitrogen fertilizer. Tartaric acids were elevated across the board in white wines so they may be a slightly less cold stable than they were last year, and winemakers may wish to adjust their winemaking techniques to compensate for that.

‘Fruit abuse,’ hairbrushes promote cluster health

Steve Price, an ETS phenolic consultant, spoke about last year’s weather from the viewpoint of a grower. He pointed out that spring heat means an early harvest, and on the West Coast we’ve seen a four-year trend toward early bloom and early harvest.

“Ninety-eight percent of the variation in harvest date can be explained by the variation in bloom date, so you know that when you have an early bloom you’re going to be having an early harvest,” Price said. ”With the trend toward warmer springs, harvest is moving from fall to summer.”

Price also said he believes warmer temperatures during harvest are influencing wine chemistry. He predicts that 2017 bloom may be later than 2016 because of this year’s severe winter and the lingering cool weather. Twelve months ago, Washington vineyards already were accumulating heat units.

He also described an unusual technique he applies in his own Pinot Noir vineyard. All premium grape growers strictly restrict the number of grape clusters per shoot, but how each grower does that is as much art as science. In an effort to concentrate fruit flavor and put all the vine’s energy into producing a limited amount of fruit, growers limit a vine’s shoots to two clusters each, some to just one cluster.

Other growers let clusters form, then drop half of the fruit on the ground, to reduce the number of clusters to the desired amount.

However, Price has been experimenting with a technique used in Europe and New Zealand which involves cutting off the bottom half of the clusters.

One advantage of this “fruit abuse” as DeScenzo calls it jokingly, is that dead flower detritus that has collected at the interior of the cluster, and which can harbor molds such as botrytis, falls onto the ground. Cluster cutting also promotes looser, more open clusters, which contributes to fruit health.

Although the technique appears a bit barbaric, when Price compared the chemistry of the cut cluster fruit to other fruit that had been limited in more conventional ways, he found only one difference. The cut clusters had increased anthocyanins, probably produced as a defense or healing mechanism when the clusters were cut. Anthocyanins assist in tannin extraction and retention, which in turn help wines age well, making the argument for adopting this unusual approach to regulating a wine’s chemistry.

And in the “science can be silly” category, Price also takes a hairbrush to green, developing clusters to brush off part of the berries, again in search of more anthocyanin development and more open clusters.

“I have several hairbrushes just for that purpose,” he quipped.

Abra, I’ve enjoyed your articles. We thin by removing berries from clusters. My experience is removing the bottom of the cluster still results in dense clusters. We strip berries out vertically if clusters exceed 200 berries in several cultivars. We have been able to totally eliminate pesticides for four vintages. I keep telling Tim our vineyard is worth a field trip.

Have you had a DNA done on your pied a cuvée? It seems often a yeast cultivar ends up being the final agent. I use no SO2 prior to ferments, and have yet to make an addition to any 2016 wines. When ferments are complete and cellar approaches 50 F I implement SO2 to control biologics.